The San Francisco Diggers were an audacious, anonymous group of street anarchists and visionary pragmatists who helped kickstart-midwife what would become the American counterculture of the 1960s. In 2021, they are little-known. But in 1966-8, such was the Diggers’ presence and notoriety that seemingly every journalist filing a story on the Haight-Ashbury district scene—even, memorably, a typically dyspeptic Joan Didion, for the Saturday Evening Post—included the Diggers in their account. “A band of hippie do-gooders,” said Time magazine. “A true peace corps,” wrote local daily newspaper columnist (and future Rolling Stone editor) Ralph J. Gleason. Allen Ginsberg and Abbie Hoffman adored them. The Beatles’ press officer Derek Taylor would later write, “[The Diggers] were in my opinion the core of the whole underground counterculture because they were our conscience.”

As the years passed, some formerly anonymous members of the Diggers have given accounts of what they were up to during this period. Actor Peter Coyote and the late Emmett Grogan published memoirs chronicling their participation in that era; Grogan’s Ringolevio is particularly notorious. These are fascinating, essential books, but there are so many other Diggers whose testimony has never been told, at significant length, in a public forum.

With that in mind, it is my good fortune to share the following conversation David Hollander and I conducted with Judy Goldhaft at her San Francisco home in November 2006 for a documentary film. Judy, a brilliant and committed avant garde dancer-choreographer-artist-activist, talks directly about who she is, who the Diggers were, and how and why they did what they did.

There has been some extremely minor editing for clarity in the transcript below, but for the most part this is how the conversation went; it has not been edited down for a general audience, and many incidents and personages are spoken of without context, or only in passing. My advice to the casual-but-curious reader is to simply let these unfamiliar/unexplained bits pass. Keep reading, you’ll like the next part.

This is the seventh interview in my series of Diggers’ oral histories; the others are accessible here. For more information on the Diggers, consult Eric Noble’s vast archive at diggers.org Planet Drum, the San Francisco-based bioregionalist non-profit foundation Judy started with her late husband (and fellow Digger) Peter Berg in 1973, continues to the present. Read more about Planet Drum here.

I have incurred not insignificant expenses in my Diggers research through the years. If you would like to support my work, please donate via PayPal. All donations, regardless of size, are greatly appreciated. Thank you!

— Jay Babcock (babcock.jay@gmail.com), September 10, 2021

Read more: “A UNIVERSITY OF THE STREETS”: a conversation with JUDY GOLDHAFT of the San Francisco DiggersJay Babcock: Where did you grow up, and how did you end up in San Francisco?

Judy Goldhaft: I grew up on the East Coast in the southern part of New Jersey. I went to college [Goldhaft graduated from Cornell with a B.A.] and then I got married. My husband Karl [Rosenberg] was a painter and he wanted to go to the San Francisco Art Institute for graduate work, so we came out here. Being a dancer, I went to Mills College and got a degree in dance.

Bob Hudson and Bill Wylie, who were part of the graduate class with Karl, were working with design with what became the San Francisco Mime Troupe. R.G. (“Ronnie”) Davis at that time was doing something called Midnight Mime Shows, and they worked with him on the props and costumes and setting up. This was like an event/performance art situation. Because these were people in Karl’s class, he was assigned to go and see it. So we went to the show and it was exactly the kind of theater that I wanted to be involved with: it was very physical theater. At that time, there was not a whole lot of physical theater besides Marcel Marceau-style mime. So I took some classes with Ronnie and got involved with being part of what eventually became the Mime Troupe.

The Mime Troupe was really a nexus for artists and poets and designers and theater people. All kinds of amazing people were involved it.

People like Pauline Oliveros, Steve Reich…

Right. Actually Steve was going to Mills when I was going to Mills. And Pauline Oliveros and Ramon Sender started the Tape Music Center, which is where Ronnie did another event/performance piece that I was part of.

With the Mime Troupe, I did all kinds of things: I did performing, I gave dance classes and movement classes, I made and designed costumes. And I also created and directed pieces. I did The Girlie Show, which starred three women: myself, Sandy Archer and Jane Lapiner. I don’t think it had much speaking in it. It was kind of a parody of all of the advertising identities of women. At that time the clothing was pretty outrageous, so we took the clothing and it made it more outrageous. The piece was basically women coercing other women to do things the way that fashion dictated them. We had a section about hair, we had a section about makeup, and we had several costume changes. In one section, we started with slides of the three of us naked, jumping, and then at the very end of it, the last costumes that we had on, were flesh-colored leotards underneath plastic clothing. We ripped the clothing off but since the clothing was clear plastic anyway, it didn’t make a whole lot of difference whether it was on or whether it was off. We had pasties over our nipples. Someone said we looked like live Barbie dolls at the very end. [smiles] It was an early encouragement to women to get control of their lives, to not be manipulated by ads and media and fashion.

The Mime Troupe at that time was in a loft on Howard Street. We performed The Girlie Show there, and we also performed it in Berkeley. I think we also performed it with [Peter Berg’s play] Center Man as part of the Traps Festival—which was about the traps that people could get into, traps that were hard to get out of. The Girlie Show was also performed some place in the East Bay at a Women’s Club. They were pretty horrified. [laughter] They had no idea what they were seeing.

I directed another piece that was about money. I don’t remember what it was called, or even if we did very many performances. It involved a grid on the floor and people walking, having to stay within the restrictions of the grid. It was about various roles that women have, like a waitress, which is a subservient and a very giving role. And there were three or four different people in that. It was mostly movement. I think it maybe had some talking in it.

An all-women cast?

Yeah. Jane must have been in it. And then I performed in a number of pieces that Jane choreographed. Jane was a dancer who we’d met that I brought over to the Mime Troupe. She did a number of dance pieces that I was a part of.

Jane was from New York. She had taken dance since she was a little girl, and had performed with some of the modern dance troupes. And she’d done the same thing I did, she got married and her husband was gonna teach at Berkeley, so she came out here. When I ran into her, she was dancing with Jenny Hunter, who was a modern dancer at the time. I went over to take some classes at Jenny’s and I met Jane and we realized that despite the fact that we had separate parents we were actually sisters. We became very close.

Do you remember anything about Billy [Murcott] and Emmett [Grogan]’s initial Diggers broadside?

They posted this sign at the Mime Troupe. It was a manifesto that said Fuck everything, including everything that you might not want to fuck, like ‘Fuck the Black Panthers, fuck the Mime Troupe’… It was signed ‘the Diggers,’ but we knew who it was.

Not long after that, a segment of the Mime Troupe decided to do street theater [as Diggers], and I was part of that group.

Were you involved with doing the free food?

My house had a very tiny stove so I cooked the food maybe once and it was horrible because it had only two burners in it. But there was an apartment that had a bunch of women who were from Antioch College in Yellow Springs. Antioch was one of the few universities at that time where you went to school for a semester and then you had a work semester. And so these four or five women had come out here and this was their work semester and they got waylaid and joined the Diggers, and became part of the Diggers. They did a lot of the cooking. Other people did cooking as well. I did some of the cooking but not a lot. Once Emmett had kind of set it up, Nina Blasenheim and I and maybe somebody else would go down to the wholesale produce market with the truck. Maybe one of the guys would be driving the truck, or maybe I would be driving the truck, and we would go to the produce purveyors and ask them if they had anything they could give us to feed people in the park. We did that twice a week. We developed really wonderful relationships with the guys at the produce markets. Sometimes there were other women who came with us. There was a whole group of people who went.

Did the produce guys prefer dealing with the women?

It’s not that they wouldn’t give food to the men. But, they enjoyed our coming. They liked us. And it was fun for us, it was interesting for us. I really liked them. So we did it. And there were some other women who went to the wholesale fish markets down in Fisherman’s Wharf.

We also did gleaning in the fields — that was quite fun. It’s a very old, traditional way of getting food. Gleaning is when they have mechanical pickers in a field, they pick certain size of whatever it is, zucchini or onions, something like that, and they drop out a bunch of them, the ones that are too small or the ones that are too big. And then if you go to the fields afterward, you can pick up the leftovers.

The free food was part of what drew mainstream press coverage of the Haight, which in turn caused a massive influx of people to the neighborhood. You guys anticipated that was going to happen.

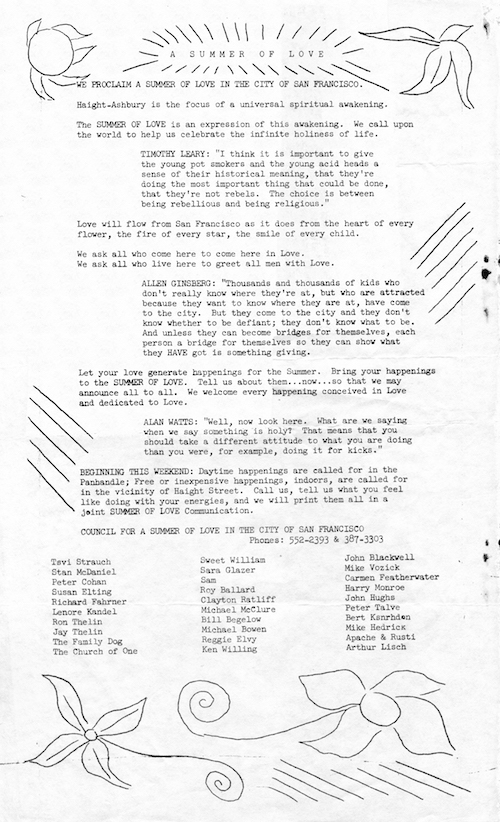

Yeah, it was kind of a media hype. In January [1967], the media said, [breathless] ‘Oh my god, San Francisco is the place to be. Come to San Francisco, wear flowers in your hair.’ So we had a meeting of the people in the Haight-Ashbury about how we were going to deal with so many people coming. The Diggers decided to kind of make it a university of the streets, an alternative anarchist culture.

We knew that all these people were coming to San Francisco, and we knew they weren’t going to stay. And we thought, well, the best thing we could do would be to kind of educate them about the kinds of things that are possible in society, and then let them go back to where they’re from, and they would carry these ideas. And that is what happened. We were quite successful in that.

Prior to that, you were doing things for yourselves and the neighborhood.

It was the same thing, really. We were trying to make a new society. We decided what we would do is provide the basics: food, and housing, and health care. The free health clinic started in the free store. And we thought if we could provide basic subsistence living—clothes from the free store, apartments because we had some apartments that people could stay in, and food because we were able to get food, and health care—that then, that would free people up. The ‘50s were the grey flannel suit and you have to have a job and you have to have money. Our effort was to disconnect people from that society, and open them up. Our idea was: If you were supported, what’s the most creative, beautiful life you could lead? That’s what we were doing.

We were not exclusive. [smiles] We said, If you say you’re a Digger, you’re a Digger. That did create some problems, but on the other hand, it opened up a lot of possibility. There were a lot of people who said they were Diggers who I’ve never met, I’m sure. And there are people who have written books about their life as a Digger and I never met them, I don’t know who they are. But that’s okay. I don’t mind, I think that’s more open.

We were very anonymous, and we were not self-promoting. People didn’t really take credit. None of the broadsheets handed out on the streets are signed, I don’t think. The Digger Papers are not signed. So who wrote what is kind of up for grabs. That eliminated, to some extent, the kind of hero worship that the media tends to make happen. Emmett had a little difficulty with this because Ramparts actually named him as some kind of Digger leader — he had a lot of difficulty dealing with the fact that he had become a “personality.” He was a very charismatic person and very energetic and he had great ideas, but he had a lot of difficulty dealing with the persona of “Emmett Grogan.” That’s why Suzanne said she was “Emma Grogan” at the Alan Burke Show, to say that the actual person wasn’t really a man, it was a woman, to play with the media a little bit.

This is why [Diggers film] Nowsreal had no narrative in it—because we thought that if you put a frame around what you’re doing and explain it to people, then they’ll only see what you explain. If you don’t explain it, then they’ll see what they see and either be confused by it or puzzled by it or turned on by it. They’ll pick whatever meaning they want from it.

What was your experience with Digger housing and apartment live?

I never lived in one of them so I’m not the person to tell you about them. I lived in a little house that was over the hill from the Haight-Ashbury. The summer when there were so many people there, 1967, every day as it got towards sunset, Peter and I would go out on the street and find somebody that needed a place to stay and take them back with us. Sometimes it was more than one person. But often it was one or two people. That was what we did. There were bigger [Digger] houses that were rented, there were flats that were rented, there were some flats that were just free available space, and each of these lasted for varying amounts of time. [Smiles] Sometimes the landlords stopped renting to us after a while.

How did the free health care clinic concept work?

There were these three doctors that said they wanted to provide health care in the Haight-Ashbury. We said, Okay we’ll set up a free medical clinic. I believe the first one was in the free store that was at Cole and Carl Street, which was called Trip Without a Ticket. One or two evenings a week, they would see people. Eventually it moved out of the free store and then into its own space. We actually would go by occasionally and check it out and see if it was still free and that they weren’t keeping records of people. Keeping records of people, although it seems like something you’d want to do in a health care situation, it was very coercive at that time. You could be pulled in, especially if you were underage—you could be found that way. So people sometimes gave alternative names. We used to check it out and make sure that they were still providing the services for free and still providing them without any coercion of any kind.

David Smith [who later ran the San Francisco Free Clinic] was not one of the original three doctors. I think maybe they were from UC Berkeley. They were pretty hip. You had to be. You dealt with bad acid trips.

David Hollander: The Diggers had support from religious organizations…?

Some. And sometimes. [smiles] And sometimes they had an interaction with us and they asked us to never come again. [laughs] We used to bake bread in the All Saints Church. They had a professional oven, and I remember cooking fish there to take to the park. I think it became the place where we cooked food.

And we did the initial tie-dying of white shirts at All Saints. That’s one of the other through-lines of what we were doing, an interest in personal creativity. Conventional fashion was about everybody wearing the same thing,everybody looking the same. Making tie-dyed shirts out of white shirts, you were guaranteed not to wear the same thing that anybody else wore. It was your creation. Quite frankly unless you’re fairly clever, you can’t really tell what your tie-dye is gonna come out looking like, you can’t make it identical to someone else’s. You may have an idea of how it’s going to come out, but it’s always a surprise, a wonderful surprise.

A woman named Jody Robbins — she changed her name to Luna Moth, and then to Luna Moth Robbins, and she was also known as Jody Paladino —she used a bunch of different names — she was a fabric artist that Karl knew, and Karl brought her down to the free store. When she saw all the white shirts, she said Oh I know what to do with those. She’d already done a lot of batiking and a lot of tie-dying. She showed us how to do it, and once she showed us how to do it, we ran with it. We did a lot of dyeing together, all the Diggers.

She and I gave a lot of classes together. She was really a wonderful artist. And later on, a friend of hers named Annie Tiedye started doing tie-dyes in the Los Angeles area.

When you talk about giving classes, where were the classes given?

At the free store. The free store on Cole and Carl Street had two rooms, and in one of the rooms was kind of a craft laboratory, where you could make things. The other room was Free Store, where you could get things.

But we also did tie-dying at events in the park. So we would, as part of an event, or giving away food, we would also have everybody making tie-dyes. I can’t quite remember but we must’ve brought some kind of heating elements, propane stoves or something, and set up pots of dye. The dye has to be hot to adhere to the material.

We made enormous banners too. When Malcolm X died [in 1965, before the Diggers existed], I was part of an event at Hunter’s Point. We brought big banners and set up tents outside, and silk-screened faces of Malcolm X that we gave people.

Those kinds of interactions continued during the Diggers…

We worked with the Black Panthers. We actually introduced the Black Panthers to giving food away, and they began their school programs of feeding kids as a result of interactions, maybe with Emmett? I’m not sure, Emmett or Peter [Berg]. I took food over to Kathleen Cleaver. We did things together sometimes. I mean, we didn’t do things together very much, but we sometimes took food to them, to their apartment.

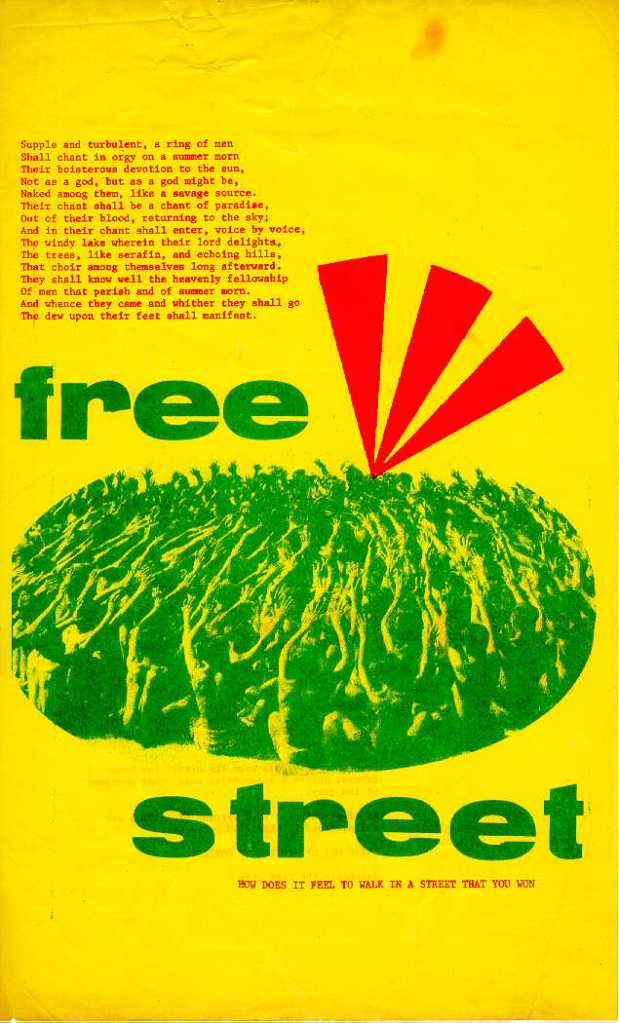

For another event, one of the things I did with another woman was to silk-screen little placards that said “NOW,” that we handed out. The concept was we didn’t want to be part of the past and we didn’t want to be part of the future, we wanted people to focus on the existential NOW. Phyllis [Willner], who was riding standing up on the back of [Hells Angel member] Hairy Henry’s motorcycle was holding one of these. They busted Henry because she was riding standing up on his motorcycle. So at the end of that event, everybody marched over to the police station at the end of Haight Street, and we raised the money to get him out.

The Diggers often acted as the conscience of the Haight — the ones who encouraged people to do the right thing, and pointed fingers when necessary. [Looking at flyer signed by the Diggers] Here’s one protesting high prices for a dance concert: “You shouldn’t have to pay for love.”

That was the Bananarantra. [smiles; chants] “Banana nabana.” The price of tickets to see a music show was usually fairly inexpensive. A group of people decided to do a concert at Winterland and they charged a lot more for it, maybe twice as much. And so we protested it, a whole bunch of people protested it. That was at the same time that people were saying that banana skins would make you high if you dried them, so we had a Bananarantra, a bananarantra mantra, that we did in front of there. I think we put out things saying “$3 is a cheap trick,” whatever the ticket cost, maybe the tickets had been $2.50 and now they were five. But it was culture being sold back to the people who made it, and we thought that was a rip-off. [emphatically] It was a rip-off.

There were a lot of people in the Haight-Ashbury who really had no idea why they were there, or what they were doing. They were the “hippies.” [smiles] We were not the hippies. We were a little bit more intense, and a little bit more clear on social activism and manipulation, and so when things happened that we thought were manipulations, we pointed them out to people.

What was Richard Brautigan’s relationship with the Diggers?

He worked with the Diggers for a while. We produced a book of his poems that included seed packets, Please Plant This Book. I think it was designed by Freewheelin Frank, maybe. And inside there were seed packets of four or five or six different kinds of seeds, with Richard’s poems on them. And we gave them away. A group of us women took them to the fire stations. We liked the firemen. You know, we were pretty hip to San Francisco history. There was a woman named Lillie Coit — there’s a Coit Tower in North Beach — and she was involved with the firemen. So we would go and do things at various fire stations as the Lillie Coit Memorial Brigade. Sometimes we would bring them flowers, sometimes we brought them cookies. We brought them these books. I don’t know what they made of them. I liked the guys, they were really nice.

How about the police?

The police were not nice but, you know, initially, the police had no idea what we were doing. It took them about a year to figure out that whatever we were doing, they shouldn’t allow it. But at first they couldn’t figure out what it was that we were doing. One time, we had these long marbleized sheets of paper. Karl was into marbleizing things and he had made the paper, and someone else did calligraphy of Lenore [Kandel]’s poem on these sheets. And then four of us went up on a rooftop on Haight Street and held the poem up, and as we’d turn the sheets over, people down on the sidewalk would read the poem aloud. The police saw that, and they thought, There’s something wrong about that. So we have to tell them to stop. [laughs]

Whose idea was it do that?

The way that the Diggers functioned, really, was if somebody had an idea, they would talk to other people about it, and if people liked it, we all did it together. Sometimes Jane made up things, sometimes I made up things, often the guys made up events that we were gonna do, but once somebody settled on an event, then that would kind of click on other people’s creativity, and they’d say, Oh if we did that, then I’ll bring blah blah blah. “I can get ice.” “Oh, I can get scaffolding. Let’s make a snowball ice mound.” It ended up being very non-hierarchical, actually.

Can you remember anything about the “The End of the War” event?

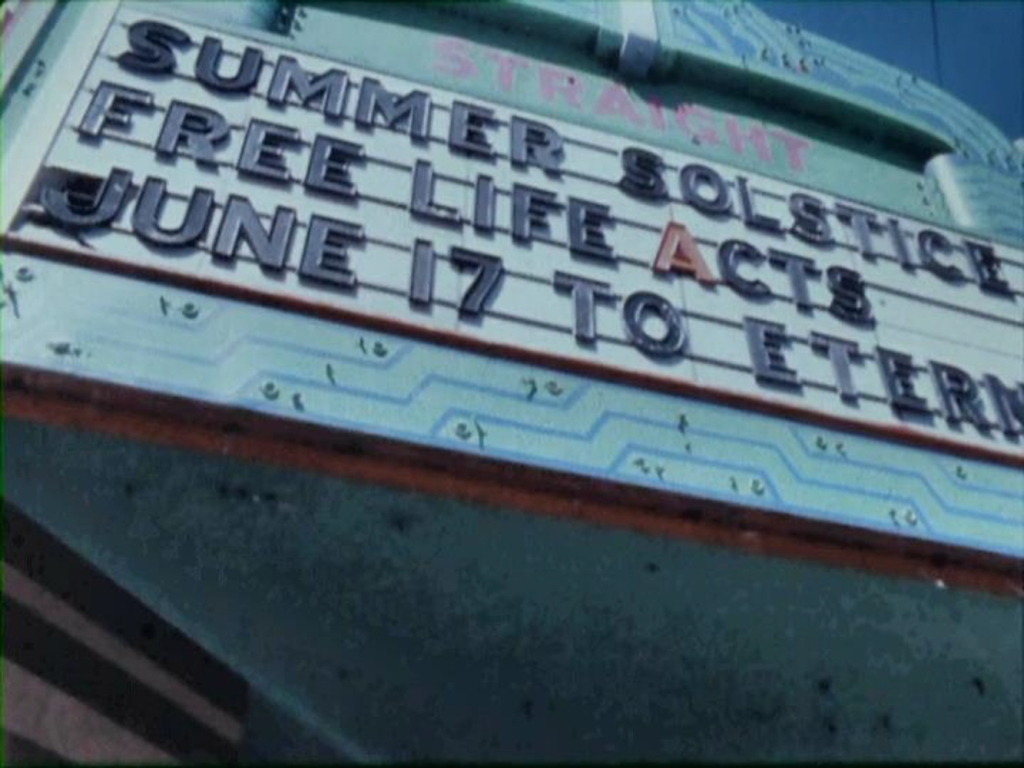

There were so many events! I can talk about some of the things that I think happened at The End of the War, but they may have been part of another event, I’m just not sure. It was definitely in the Straight Theater. Bruce Conner was running for mayor at that time and he was there, giving his mayoral ‘vote for me’ speech, and he listed all the things he was for: apple pie, lemon meringue pie, lots of very American foods and pies and things like that. It was very funny. I think that’s the event where Peter put together loops of disaster tapes, natural disaster tapes. Volcanoes erupting, hurricanes… We made black-and-white film loops of them and showed them on the screen.

We gave out our free money at that event. A ceramic artist made little coins that said ‘free money’ and they had winged penises on them. A number of the women had perfumed oils in bowls, warmed up, that we would put on people. [motions] Make them smell good. [smiles] A sensuous thing. We also had branches of trees that we handed out so that the audience ended up looking like a little forest. It was pretty amazing. People who were in the Army came to the event. Steve Miller played ‘When Johnny Comes Marching Home,’ and they played it a number of different ways. That was very nice. I’m not sure—I think I might be mixing up two events—but at one event at the Straight Theater, we had cargo nets that we hung from the balcony, and let people climb up on them.

Cargo nets! Where did those come from?

Who knows. Somebody got cargo nets, and we hung them from the balcony. A lot of the things we did [in those days] were actually quite dangerous [smiles] and quite on the edge. You could get hurt. But nobody ever did. We must have had the right vibes. [chuckles] Or something.

At one event, we did Jane’s other dance, which was called Waiting. There were a lot of lifts in it — people were lifted up by other people — so we made signs of various things being supported, like signs at a protest rally or political convention. I’m just not sure if this was the same event.

The Diggers had an interest in bellydancing—where did that come from?

I did that. Why bellydancing? Because we were living in a society that was very Puritanical, and there was very little, I know it’s hard to think of it now, but at that time, we’re coming out of the ‘50s, and the ‘50s was really very repressive and very restrictive. We were involved in sensuality and things being beautiful and sensuous, and bellydancing seemed to me to be beautiful and sensuous, and it was a celebration of bodies and sensuality.

Lenore had done some bellydancing. She had been a folksinger and she sang in some clubs and in one of the clubs, in New York I think this was, the Greek owner had taught her to bellydance. So she taught me the basics of bellydancing and I taught a bunch of people. We began doing bellydancing, at a lot of events. One of the things I wanted to do at the “Invisible Circus” was to have this group of bellydancers break out from behind a wall.

In Nowsreal, there’s a group of bellydancers on that flatbed truck. Are you on there?

Yeah. I think I’m [the one] wearing a polka-dotted raincoat. That was the summer solstice of 1968. At that point, the Diggers had kind of evolved into Free City. There were political conventions going then, so we did a Free City Convention. By that point, we had moved beyond the Haight-Ashbury. Haight street had been made one-way, so that meant the police really were in control of the street. They could just stop traffic at both ends. So we thought the only way to continue with our desire to make a new society, a changed society, was to move out of the Haight-Ashbury. That’s why we did poetry readings on City Hall steps for three or four months.

After the Invisible Circus, we had a meeting, about 8 or 9 of us, about what we should do next. [shakes head] That had been so much fun. We had to do something—what shall we do next? Lenore Kandel said we should consider a planetary holiday, and noted that the summer solstice was coming up. Although of course it wasn’t coming up for six months or so. And so we decided to do all kinds of things for the summer solstice.

Previous to that, the solstice and equinox events had mostly been in Speedway Meadow or the Panhandle. But now, we were trying to move the effort out into other neighborhoods. We made coalitions with people in the Mission district, people in Chinatown, the activist kind of gangs [smiles], the Hua Ching in Chinatown and the Mission Rebel. And that’s why, as you can see in Nowsreal, we were on a truck. The bellydancers and the music were going from park to park, from neighborhood to neighborhood, across the city: the Panhandle in the Mission District, Delores Park in North Beach, Washington Square. And there are shots of us driving through the Financial District. Driving through the Financial District, encouraging people to go to the Park, telling them that it was a holiday.

At that time, nobody had any awareness of planetary holidays. Now even on the weather report they tell you, Well tomorrow is the equinox, the first day of fall, or spring, but at the time nobody had much awareness of it. When we were going through the Financial District, the film makes very clear the repression that was going on: the guys looking at the girls, kind of drooling, licking their lips. They didn’t get this in their usual day-to-day life, they didn’t get to see a lot of flesh, [laughing] especially in the Financial District. We were yelling to them, Go to the park! It’s a holiday! It’s a planetary holiday. Today is the solstice. Go to the park, enjoy yourselves!

You guys were into planetary holidays.

We did that on purpose. There were a lot of lines in the Sixties and one of the lines was to lead a more natural life, to be in tune with the planet, in harmony with the planet. So we celebrated all the planetary holidays. We did things on Haight Street, we did things at the beach. We often watched the sunrise and the sunset. One of the sunset events we decided to do was at Land’s End, which is on the coast, and it’s very rocky. We went there with some people, and they were all very disappointed: Where are the people? You said this was going to be an event and there’s nobody here! So we said Well, listen, we’re gonna do this thing. We had handed out little sticks that were sparklers, and as the sun went down, all over that cliff, there were sparklers lit. So you couldn’t see the people—but obviously there were lots and lots of people there. It was a wonderful event.

One sunrise, we went up to the top of Strawberry Lake in Golden Gate Park. Somebody had made bags with candles in them, lighting the way up to the top of Strawberry Hill and Golden Gate Park and we all met up there and watched the sunrise, and played musical instruments, blew a conch shell, generally made a lot of racket.

Some of the events were pretty outrageous. One of the summer solstice events we did in Speedway Meadow and we took a lot of props. Lenore was very good at getting things given to her, and she had gotten a lot of windchimes. She hung them from the trees, just randomly. And she was big on pennywhistles, somebody had provided her with pennywhistles. And a bunch of us made reams of tie-dyed material, which we just plopped down somewhere for anyone to do what they wanted with. During the day, I went back to the place— this is to give you an example of how things were at one of these events, so much was going on that you couldn’t possibly know what was going on all the time—I went back to where we’d left tie-dyed sheets that we’d sewed together, and people had made it into a teepee. And another time they had made it into a garden. Then they had made a fence out of it. And it just kept evolving. People changed it, people came and did something with it and then left. I have no idea what happened with the material. I hope somebody just took it and enjoyed it. [smiles]

At the end of the day, after an event like this, we’d all get together and say, Well what did you do? And people would rap about what they had done. And what they had done was more than you can imagine now, looking back, and sometimes less than you can imagine. [chuckles] In Nowsreal, at the beginning of the part about the Solstice, there’s a long shot of the skyline of San Francisco. The reason that that shot is there is because someone had gotten flares, and 12 people had gone to the top of buildings and they were going to shoot the flares off. [laughs] This sounds reasonable. So someone had gone to film, or shoot, these flares coming off the top of these tall downtown buildings in the morning. Right? Well, but there was nothing in the photograph. There’s no flares. What happened? Well, when we got together later, somebody said, God! It was so exciting. I had to get to the top of this building. I managed to do it, I got myself on to the roof, I got there, I had the flare and I struck it, and I held it up…and it was one of those highway flares. It made a little red flare. But it didn’t make a big FLARE, which is what we had hoped it would. So, you know, things sometimes didn’t work out. [smiles] It was funny.

Can you talk about some of the other daily ‘free’ stuff you were involved in? You were talking about teaching bellydancing…

Mostly I did it for particular events. We did have dance classes, though, everyday. Jane gave dance classes everyday, and sometimes I gave mime classes. And we all did bellydancing, but it was not a regular thing, it was more for a particular event, we would teach a bunch of people how to bellydance. And it was wonderful because they were all shapes and sizes of women. We were really excited to have a lot of different sizes and shapes.

Were you guys teaching yoga? There’s that scene in Nowsreal…

We’re doing modern dance. But people were involved in yoga too, yeah.

Okay. Going back to some people who were involved with the Diggers, who aren’t alive now. Richard Brautigan…

He helped design events. We worked with a bunch of artists and poets. Lew Welch, he was one of the Beat poets, he was around. He was married to Lenore for a while. I really liked him a lot, but I didn’t know him very well.

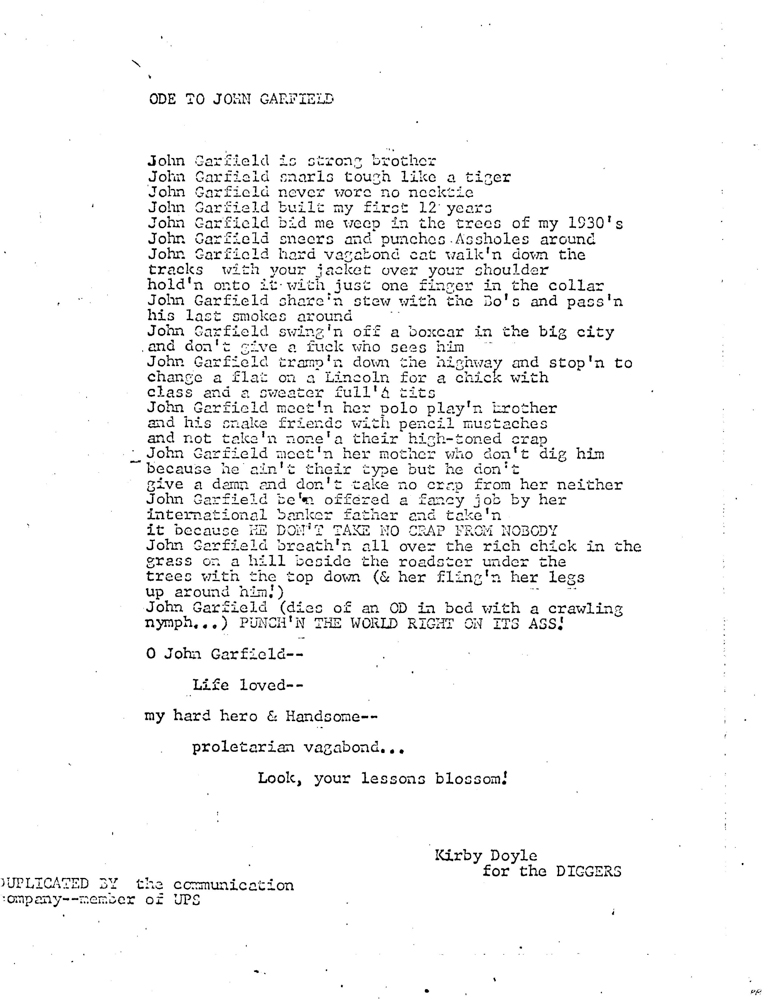

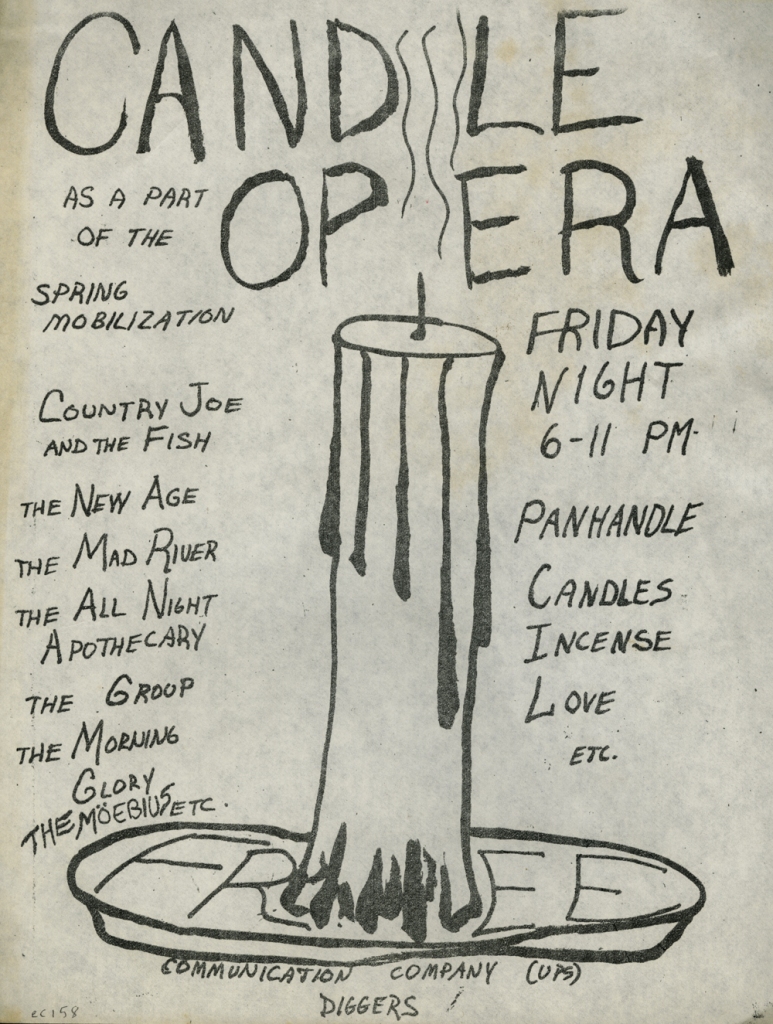

Kirby was a marvelous poet, and a crazy person. He wrote some poems, one about John Garfield, that we read at the “CandleOpera.” He actually lived with the Diggers, he was one of the Diggers for a long time. He was a very intense person, and he was very creative. He had a girl child with one of the other Digger women whose name was Tracy and they named her America. That’s an intense name.

What do you remember about the CandleOpera event?

It was wonderful. [smiles] I don’t think I can describe it properly. It was an evening event in the Panhandle. People read poems. [looking at the flyer] I guess there was music, it says there was music. There were no lights in the Panhandle, so we put candles around in the trees and things so there was a certain amount of light. And there was a stage, and that had lights. Or some lights? I can’t be certain. There was incense and there was dope. It was one of those events that could easily have turned into something terrible. But it didn’t, so it was wonderful. In our life today, we’re rarely in places where it’s very dark, and it was very dark at the CandleOpera. I remember that. The night is very dark in the Panhandle. And you know, the Panhandle was not a nice place at night. People got raped there, so people didn’t go there at night. And for the Candle Opera to be there was to open it as a useable space. It was wonderful. It was scary and it was exciting. It got your adrenaline running.

That’s almost a metaphor for what you guys were doing.

David Hollander: The Invisible Circus was almost like that—

Yeah, it was scary. It was a miracle that nobody got hurt. [smiles] The amount of people. That elevator was stifling, that elevator with all the plastic strips in it. I don’t know why nobody got trampled in it.

Y’know, also, in the sanctuary at the Invisible Circus, we showed Night and Fog.

What was the thinking behind that?

[shrugs] Why not? It’s the intensity of life, the things you have to deal with in life. People also made love on the altar there too. You can see why we didn’t last more than 24 hours there.

Another aspect of the events is that they were very sensualist. You were engaging all the senses — sight, scent, sound…

I think everybody was a sensualist at that time. [contemplates] Everybody was dancing. Before that, when I was giving dance classes at the Mime Troupe, not too many people knew how to move their hips. And their arms—nobody used their arms, either. You’d see a group of people dancing and you’d see maybe one person moving their arm up. Up ‘til then, there had been swing dancing, there was jitterbugging. But as part of the ‘60s, people began exploring their own movement, what it felt like to move their bodies.

You guys were unlocking spaces, opening up minds and bodies—

You want to get people to open up and do whatever they wanted to do. I loved watching the dancing then because people really were doing creative exploration. A lot of interesting dance happened there—people feeling the music.

And, a lot of alternative health things developed out of the Sixties. People were trying to do things in a more natural way. Chinese herbal medicine—herbal medicine per se—was being explored. And that was very hard to do. People really didn’t accept things like that. It was hard to do. And babies began being born not in hospitals but at home.

Natural childbirth, right.

In some ways it was very progressive but in others it was a revival of ways things had been done—

Before the Industrial Revolution. We were very into exploring the long-term ways that people who were able to survive did, and the things that they did, we revived them. We did canning, for example. We got a lot of tomatoes, and we canned them all. And when people moved out of the city and back to the land, canning became a big way to preserve food.

Digger Bread is whole-grain. There was a natural foods movement at that time but it was really very small, and people wanted to do things in a more healthy way and without preservatives. We made Digger bread two or three times a week, or at least once a week. We were given a bakery to use. The recipe for the bread was a whole wheat bread, a healthy bread. At that time you would’ve been lucky to find rye bread, let alone… It was little balloon white bread was what was around. A lot of people learned a lot about food in the Sixties.

And you communicated using an old method—the broadside.

I think it was Arthur Lisch who got the Gestetner machine…

Who was Arthur Lisch?

He had a job working with the American Friends Service Committee, but he liked what we were doing as Diggers, and he got involved. He provided a lot from the access he had.. And he also was an artist, so he had a nice sensibility. He did a lot of things. He ran one of the free stores, I think. I believe that he got a Gestetner. I wouldn’t swear to it. It was either he or Don Cochran. But I think it was Arthur.

We took our Gestetner down to some of the schools, and had the kids write instant poems and things at lunchtime. We put out this newspaper for three months. We made little “Free News” boxes, there was one up at City Lights, there were other ones in the Mission District and on Haight Streets. So you would Gestetner up these different pages and then staple them together, they’re kind of like the Digger Papers that the Realist put together, and then go distribute them.

We actually took those sheets to the Gestetner company. They had no idea that their machines were capable of doing what we did. Like we put a peacock feather on the Gestetner and put the top down and Xeroxed it in color. And they were amazed. They were very beautiful sheets. We asked the Gestetner company to let us keep their machine, which hadn’t been paid for in full, and they said, No.

So we liberated it.

Thanks again, Jay, wonderful

I wonder who the women from Antioch were that Judy mentions, I probably knew them. I was in SF in the summer of ’67, at the beginning of the Diggers, then went to France in the fall on a Fulbright to translate Max Jacob. Come May ’68 and the revolution I had my bell rung big-time, still sounding in my head

LikeLike

thanx bro :)))

LikeLike

JayBab & David – These secret histories are a joy – and no longer secret. You’re doing the work – thanks!

LikeLike

she’s right, the diggers started everything, and we certainly looked to them from detroit to know what to do next. thanks, jay, for the great work!

LikeLike

amazing – and yet so familiar. I feel like I was there.

LikeLike