I interviewed the late Peter Berg at his San Francisco home in November 2006 with David Hollander for a documentary film project.

Berg was reluctant to speak yet again about the Diggers — he had given many interviews through the years, and dreaded what he called “the 7s” — years ending in “7,” which always marked a numerically significant (10th, 20th, 30th, on and on) anniversary of the 1967 Summer of Love and for him meant yet another round of fielding media asks for interviews about the Diggers’ role in the Haight-Ashbury scene.

In 2020, the Diggers are little-known. But in 1966-8, such was the Diggers’ presence and notoriety that seemingly every reporter filing a story on the Haight — even, memorably, a typically dyspeptic Joan Didion, for the Saturday Evening Post—included the Diggers in their account. “A band of hippie do-gooders,” said Time magazine. “A true peace corps,” wrote local daily newspaper columnist (and future Rolling Stone editor) Ralph J. Gleason. “A cross between the Mad Bomber and Johnny Appleseed,” said future Yippie Paul Krassner in The Realist, “a combination of Lenny Bruce and Malcolm X, the illegitimate offspring resulting from the seduction of Mary Worth by an acidic anarchist.” The Beatles’ press officer Derek Taylor would write, “[The Diggers] were in my opinion the core of the whole underground counterculture because they were our conscience.”

In the decades afterward, everyone wanted to interview Peter Berg because he had been there, he had done things, and most of all, because he had remained brilliant and charismatic, post-Diggers. Berg was a playwright-dramaturge and anarchist tactician who had a street sense, a sense of history and a sense of humor; a short, sometimes brusque guy with a big, creative, poetic mind who gave tremendous quotes.

Born in 1937 (another “7”), Berg was in his late 20s as the Haight-Ashbury “uprising,” as he called it, rolled into being in 1966. He was somewhat older than the drop-out “flower children” and teenage runaways of the time. He was also somewhat younger than the Haight-curious North Beach bohemian poets, painters and beatniks, most of whom were in their 30s and 40s. Having coined the term “guerrilla theater” during his productive time in the radical San Francisco Mime Troupe, Berg found his role in the Diggers, manifesting maximum social joy and welfare through a set of deceptively simple ideas whose range of application seemed boundless.

In 2006, after many phone calls, emails, postcards and a shipment of Arthur No. 13, David and I scored an audition with Berg to conduct an interview. We passed, and, not long afterwards, on camera in his kitchen, Berg gave us — performed for us — one of the best, most comprehensive interviews regarding the Diggers that he ever did. He was on for two hours, and he knew it. I hope the following text, basically a transcript with extremely light editing for clarity, gets that across.

Berg died in 2011. Planet Drum, the San Francisco-based bioregionalist non-profit foundation he started with his wife (and fellow Digger) Judy Goldhaft in 1973, continues to the present. Berg’s contributions to bioregionalism were foundational and visionary; his work persisted across decades, and was a natural continuation of his Diggers work. Read more about Planet Drum here. For more information on the Diggers, consult Eric Noble’s vast archive at diggers.org

I have incurred not insignificant expenses in my Diggers research through the years. If you would like to support my work, please donate via PayPal. All donations, regardless of size, are greatly appreciated. Thank you!

— Jay Babcock (babcock.jay@gmail.com), Sept. 16, 2020

Read more: A GUIDING VISION: A conversation with PETER BERG of the San Francisco Diggers

Jay Babcock: What kind of family did you grow up in?

Peter Berg: My mother used to call herself a ‘parlor pink,’ which was a variety of Red. My father was known for being able to recite whole pages from H.G. Wells’ Outline of History. At that time that sort of indicated that he might have been a leftist, but I’ve called him a barroom socialist because my father was also an incredible drunk. My own feeling is that they were immigrant folk socialists. My brothers enlisted in World War II as Navy fighter pilots. They called it the “War Against Fascism.” [That kind of language] was in the air at the time. It wasn’t theological. Sort of FDR/Socialist “New Deal,” that kind of thing. That’s the kind of politics that were around.

You went to University of Florida to study psychology…

I didn’t go there to study psychology, I went there to be a college person. I think I was 16 at the time. 15 or 16, because I’d been skipped ahead at school. I had to choose a major, and by sophomore year I’d decided that one of the least venal things to choose was psychology.

It was a fairly large university, 10,000 or so, but the group of people who were ‘alternative’ was so small they all knew each other. It wasn’t more than a couple dozen. There were a group of us who wanted to provoke, to insinuate, that integration was overdue at the University of Florida—it was 1957, three years after the Civil Rights Act— so we pasted up posters with the slogan ‘Integrate in ’58.’ We pasted those up at night. We didn’t want to be seen. It was not public.

You put them at night because you had to, or to …?

To avoid being censured. To avoid being beaten up by fratboy football fan types. In fact, the editor of the school newspaper made his reputation by posing as queerbait, getting propositioned by homosexual professors, developing a list of them, and then outing them and getting them all fired.

How did you get to San Francisco?

The main thing I did academically in college was to read novels. I read all the authors straight through. One of the things I picked up was there was an American ethos, and I wanted to go search it out. So I made hitchhiking forays to different parts of the country. One of them was to the Midwest, to see the “real” America. I worked in a factory that made flexible metal tubing. I hitchhiked to San Francisco. San Francisco was a destination for me because I had read ‘Howl’ in college, shortly after it came out. In fact, I read Howl the night that Fidel took Havana. I know because we were in a bar to read Howl together, my friends and I, and somebody came in with a shortwave radio and threw the aerial up in the air and in Spanish it said, Fidel Castro has taken Havana.

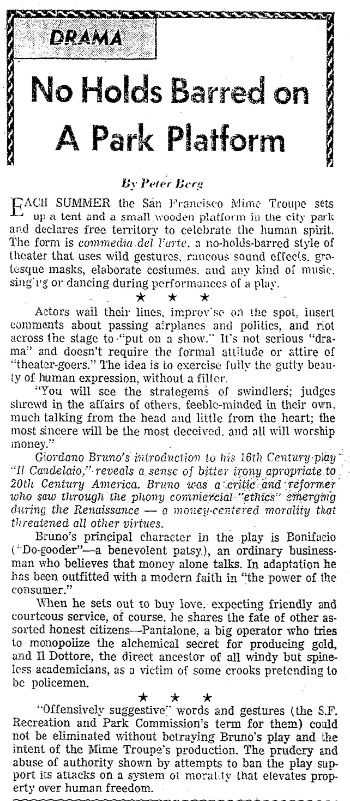

So, I made hitchhiking forays. I went to the Pacific Northwest, I was on Whidbey Island in Washington. I jumped a lumber freight and came down to the Albany trainyard, in Berkeley. I met some people, took some LSD, decided to go to Mexico. Spent a month in Mexico, broke. Came back to San Francisco, pretty shredded mentally. A lot of reverse culture shock, coming back to this very materialistic California culture from Guadalajara in 1963, maybe 1964. I got a job with the City of San Francisco, and while I was working for them I heard about the San Francisco Mime Troupe from someone, I forget who, and just walked in and told them I was a writer, director and an actor. And the very adventurous director Ronnie Davis—R.G. Davis—handed me a book that was a translation of Giordano Bruno’s late Renaissance play Il Candelaio [The Torchbearer, 1582], which was really a philosophical treatise in the form of a play—a very old way of writing. It’s Greek dialogues, a five-act play of dialogues. Absolutely unplayable. It was not theater. But he asked me to make a three-act, free Commedia dell’arte from it—it’s the form of theatre Ronnie had pioneered in this country. It’s a Renaissance, Italian form of acting where there are stock characters: the doctor, the clown, etc. And I did. And we rehearsed it; one of the lead actors was Luis Valdez, who went on to form the Farmworkers Theatre (El Teatro Campesino) for the grape strike in Delano in 1965.

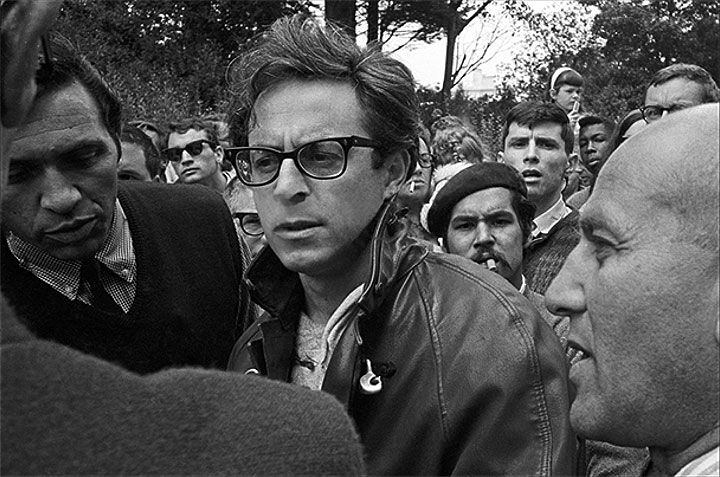

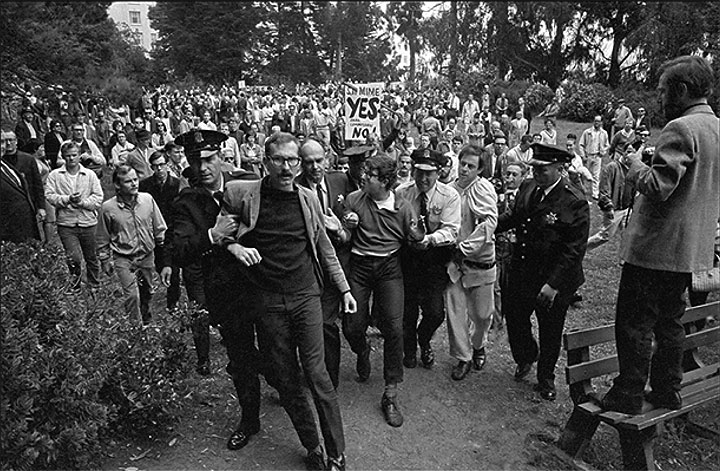

Well, while we had been rehearsing it, a dispute had occurred between the city and the San Francisco Mime Troupe. The dispute was whether or not we would receive our share of the San Francisco hotel tax, which is a form of promoting the arts. The city decided not to give us the hotel tax money that we’d gotten the previous year. So, the director’s response was to not apply for a permit to do a free play in the park. And we knew we would get busted. I mean, by the time we were all in the truck, headed for the park, we more or less highly suspected that the police would be there. And somebody, or several people, invited most of the people who were later to be called the New Left in the Bay Area to come and be an audience for the play, and react if the police attempted to stop it, if there was a dispute about attempting to perform without a permit. We arrived, and of course I’m all involved in the idea that I wrote this thing and it’s going to be performed, and frankly I’d never written a play before in my life, and I was very excited, very ego-identified with it as the playwright, and we show up and there are black mariahs—paddywagons—all over the place.

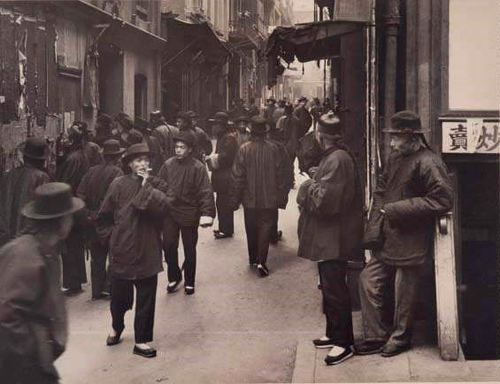

The director, who did not possess a tremendous amount of physical courage, but was kind of playing to his troupe and to this New Left audience, said, Give me the costume for the lead actor, I’m going to be the one who jumps on the stage and announces the play. So we set up the stage. Still nothing from the police. Got into costumes. Still nothing from the police. The audience gather around, anticipating that this is going to provoke a riot or something, an arrest. And the director jumped on the stage and said, “Ladies and gentlemen, the San Francisco Mime Troupe presents—a bust!” And the police, on cue, came forward and arrested everybody. Or, arrested him, dragged him off. There’s a great photo of all of us looking kind of stunned. Me, looking like, What happened to my play? Or at least that’s the way I see it.

Photo: © Erik Weber

The New Left people were just galvanized. It was a polarizing event that made a unity out of this group of people who were old Communists, Beats, gays, proto hippies, musicians, the underground newspaper the Berkeley Barb, all these people were suddenly made the same people, by that event. And all yelling, Stop, stop, you shouldn’t do this. And also all knowing that it was staged. You hear that word “staged”? That’s kind of key to what happened with the Mime Troupe next.

That event led to benefits for the Mime Troupe, who had no money. And our business manager was Bill Graham who at that time was called William Grajonca, he had his Polish name still. He wanted to be Sol Hurock when he grew up, Sol Hurock was a big promoter in New York. And he had this idea of having the benefit. It had an incredible array of performers: Frank Zappa’s Mothers of Invention—I requested that they be there. Lew Welch, the great San Francisco poet, was there. Timothy Leary. Some of the San Francisco Sound people, I think Big Brother was one of the groups. And others. And people lined up. Thousands of people lined up for a dinky studio on Howard Street that only held 200 or 300 people maximum. This was incredible. And suddenly this event was not only the creation of the New Left, but it was a statement of the counterculture. Bill Graham saw it, and he had a revelation: Whooooo, herein my future fortune lies. And we looked at it and thought, we’re really doing what we’re supposed to do as a radical theater company: we provoked an arrest, it annealed the New Left, and it created a focus for the new culture, which some of us who lived in the Haight-Ashbury had seen developing around us. We were pot smokers and acid rock-oriented. We listened to Sandy Bull, and Billy Higgins, Ravi Shankar, getting all those Eastern half-notes and quarter tones, all of that. Janis Joplin was walking around on the street of the Haight-Ashbury at the time. I was in a commune at one point with Chet Helms, who founded the Family Dog. He was a dumpster-diver who lived in the Haight-Ashbury.

Anyway, we knew this new culture was there, we knew this phenomenon was occurring, centered in the Haight-Ashbury, so after this event, we dramaturges sat together and tried to think it out. What is this, in terms of breaking down the fourth wall? How is this a historical follow-through for Antonin Artaud on one hand and Bertrolt Brecht on the other? How did these two come together in this? What do you call this, when you provoke riots and use the audience as members of the cast? When you can stage events that brings the audience on the stage—but there is no formal stage? But it’s a theatricalized event…? It’s all new. So I called it ‘guerrilla theater.’ And Ronnie heard that phrase, and wrote an essay about doing Left provocative theater. That wasn’t what I saw. I saw it as being deeper than that. And I began writing plays that now were for sure plays except that a lot of the dialogue was spontaneously derived from the performers—we had some really great performers at the Mime Troupe at the time, I’d say there were at least a dozen good performers, and a couple who were really brilliant. Anyways, put these people together, I gave them a context, and we began improvising dialogue.

Note mention of Berg in Footnote 1.

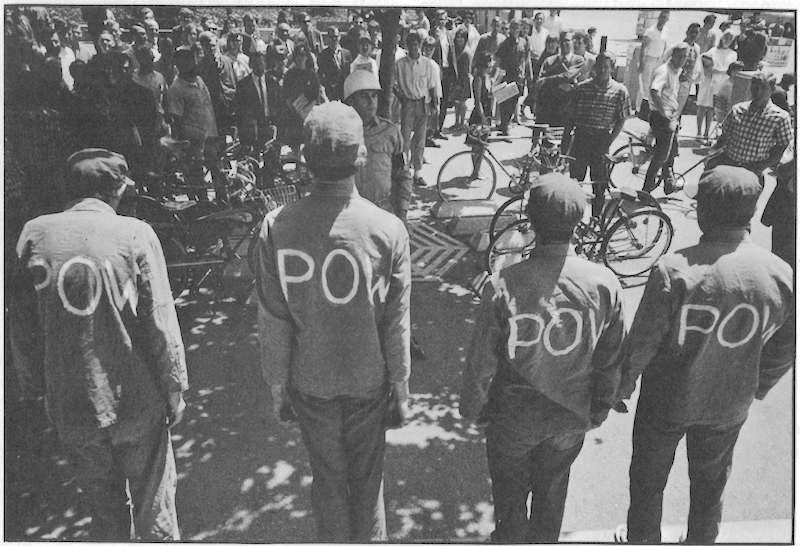

At the same time I had in mind a couple of ideas. One of them was based on a short story by a former German prisoner of war who was a literary hero of the postwar era in Germany, Wolfgang Borchert, he wrote a number of short stories, one was titled The Dandelion, based on his experience in a Russian prison camp. It was about military prisoners who craved so much to have some sort of human contact that they will take extraordinary risks, and one of them risks getting out of line to run over to where a dandelion is blooming, to look at the flower. And is beaten to death. It must have actually happened. So I wrote a play titled ‘Center Man’ about a military prisoner of war, a German prisoner of war who’s in an American prisoner of war camp, and I thought people will look at this as being exotic but it’s actually what’s happening in Vietnam. So it was a way of talking about Vietnam without directly talking about Vietnam. The guard has the prisoners do exercises. One of them reaches out to grab the flower, and the guard beats him to death. And a friend of mine designed a set that was made out of exhaust pipes, the whole exhaust assembly, rusted out, as the background. And as I was rehearsing this play—this was more scripted than the ones that followed—as I was rehearsing it, Ronnie, who had this directorial brilliance, looked at it and said, ‘These guys are just talking to each other, we’ve gotta have them doing something.’ I had them running around in a circle. He said, Put shower shoes—clogs—on them. Make it really loud. So now they’re going [claps stridently] [yelling] “Run around!” and they had “P. O.W.” written on the back of their fatigues, and the guy’s got a white helmet and MP [Military Police] on his arm, he’s smacking them while they’re running. Well, by the time he hits this prisoner and kills him, it was a pretty profound, emotional thing. A lot of it derived from the sound of these shower clogs banging on the stage.

So where do we bring this, as guerrilla theater? The Free Speech Movement (FSM) is in full bloom at UC Berkeley. Free Speech Movement: students have a right to say whatever they want to say. You can’t control speech. Students aren’t going to school. Nobody’s going to class—there are no classes. Even the professors have walked out. There’s a huge stage set up in Sproul Plaza and all kinds of FSM people are giving speeches— Communist Party people, civil rights leaders, anti-war, student freedom, Mario Savio. That day when we finally get over there is at least a couple of thousand students around the stage.

So we show up in a VW van. No idea what we’re gonna do. None at all. We’d just heard that the FSM thing was going on. None of us had been there. I go out and I suss it out, and I see that there’s a big stage with people on it and a lot of people in front of it and a big plaza. So I come back and tell the actor playing the guard, ‘March the guys out into the middle of that crowd. Clear the crowd—push the people out of the way—and start doing the play, without any announcement. Just start smacking these guys around and having them clog in a circle, and then kill that guy at the end.’ The actor asked, ‘And then what do we do?’ ‘Well, then we leave. We’ll just get back in the van and drive away.’ ‘Well, who’s going to know it’s a play?’ ‘Nobody’s going to know it’s a play, or if they do, they’ve never seen any kind of play like this before. It’ll be an experience. They’ll participate in the cruelty of the guard. They’ll observe it, not knowing if it’s true or not, they will observe the murder of a prisoner, not knowing if it’s true or not, and we’ll see what happens. This is guerrilla theater.’ [chuckles] We hadn’t ever done it before, but we’re pretty highly trained spontaneous performers.

So the guard on the way out, he has them pick up cigarette butts. He’s shoving people out of the way, saying, Get out of the way, get out of the way of my man here. Pick that butt up now! You know what’s gonna happen if you don’t. So people start clearing this path. And they clear the path until the four actors—the guard and three prisoners—[actors with] no set—go into the middle of the plaza. The guard had the authority to begin the play whenever he wanted. So he begins the play. And people start backing away from the circle, physically getting away from this behavior and saying to each other, What’s going on? They can’t allow this, can they? Is this like ROTC? What’s happening here? Does anybody know…? Is anybody in charge of this? Uh, who let them here? That’s American military isn’t it? Uh, who are those guys? W-what are they doing? I was there in the crowd, I heard these comments. I couldn’t believe it! I was delighted. My ears were about to spout blood. It was extraordinary. And then they killed the guy. And people start yelling: You can’t do that! Does anybody see what’s going on here? And there was sound with it. You know, when he kills him, he hit his club on the ground so it goes POW. And then there’s this sucking in of breath, screaming, girls are crying, students… the people on stage have stopped talking. This is like prohibited criminal behavior going on in their ivory tower, and they’re witnessing it. And they don’t know how to respond. What do I do when I see a military man murdering somebody? So then the guard orders the other guys to pick up the body. He walks them off and back to the van. And we drove out of there.

We get in the van and we’re saying to each other, WOW. [laughs] It was like throwing a stick of dynamite into something. This isn’t show business man, what are we doing? We gonna get away with this? That’s what we’re saying on the way back to the place. So then we tell the people at the Mime Troupe about what we did. Mouths dropped open. It was like, You didn’t tell them it was a play? You didn’t tell them it was the Mime Troupe? No.

So now this is more than free theater in the park, this is this guerrilla thing. We’re gonna be doing this guerrilla theater thing. And Ronnie at the time, to his credit, allowed me to do whatever I wanted. He gave me a position there. After that we did a guerrilla theater piece… Well, one of them was to take a scene out of a Jean Genet play titled The Screens, and do it in the bus station, without telling anyone it was happening. It’s full of criminals of various kinds, and we just had it done, and a cop saw it going on, and just from the behavior of the play, said, Y’know you gotta stop doing that, you can’t do that in a bus station. You can’t shoot drugs sitting in a seat waiting here for a bus. [chuckles] That’s the way he treated it. But that one wasn’t really so sensational.

One other play we did was called ‘Search and Seizure,’ at a rock club called the Matrix, on the same bill as Country Joe and the Fish. The guys in that band did not know what else had been booked, so the first night we did it, they watched along with the audience in the club. It was largely improvised dialogue—improvised in the studio, and then written down so people had their speeches. Some notable things about it: the characters were a doctor strung out on heroin, a hippie who had dropped a tab of acid, somebody with some marijuana and somebody on speed. They’re pulled out of the club group and put on stage by two people who purport to be narcotics detectives. So they’re pulled away from the tables they’re sitting at, put on stage, and face the audience, where this interrogation begins. If you did this one quickly, nobody thought different: it was real. If you had any pauses or laughed, you blew it, but if the actors acted like, what’s going on, where’s Country Joe, if they were like that, the detectives were hard cop/soft cop, and you got into the rhythm of it, people watching, they thought they were watching the real thing. Or if they weren’t watching the real thing, this was the realest thing they’d ever seen! Country Joe told me it made him paranoid, he was never going to watch it again. I mean, that’s how effective it was. [laughs] Emmett Grogan was one of these people. I think he was the speed freak. Anyway, they all get busted, they tell their stories of why they’re there: what are you on, what does it make you feel like, why are you doing this? The cops insult them, they call them enemies of society, etc. And then they lead them off at the end, they lead them to the back and out the door. Nobody says anything to the audience—nobody says, You just watched a play, or, Now it’s over and now we present Act 2. That was really good, that one. Like 15 or 20 minutes. The actors would improvise on their own improvisations, they would improvise on their own lines. Some of them got very involved with their lines—it was their chance to be a playwright.

You mentioned Emmett Grogan. Who was Emmett Grogan?

Emmett Grogan was one of the people that walked into the Mime Group the same way I did. He came in and purported to be an actor. He claimed to have been to a film school in Italy, which I doubted, because he didn’t pronounce “Cinecittà” correctly, so I thought he had not actually been there. I would learn later that almost everything that came out of Emmett’s mouth was at least an exaggeration if not an outright fabrication. But that was somewhat forgivable, considering his charisma; his charisma was substantial. More than substantial—he was probably the most charismatic person that I had ever met. And he was enamored of that ability. He was not a good actor, onstage. He was an extraordinary life actor. I created the term ‘life actor’ to describe him. It’s part of that thing about lying, or misrepresentation or whatever. He would bring things off to see them happen. What if somebody moved like this? What if somebody said this as an answer? That’s the way he operated. And he was, I don’t think he was fearless, but he was stronger than most of the people he ran into in San Francisco. He was from Brooklyn or Hell’s Kitchen, New York, I’m not sure which. Had a New York attitude. Tough, New York, gang…? I did meet some young mafiosa that were his acquaintances, so he had dipped into that life to some extent.

I cast Emmett in ‘Search and Seizure’ and in something I did only one time in a Berkeley coffeehouse that was about the impact of cybernetic culture. This was sort of prescient to do this because almost nobody was even writing about computers in 1967, and the best things I got a hold of [on the subject] were by philosophers. There was an essay titled A Prolegomena to Androidology [Michael Scriven, 1960] that had a dozen tests for whether or not something could only be done by humans or could also be done by machines. The conclusion was that machines could do anything that humans did. So I wrote a guerrilla theater piece called “Output You” and in it there were a woman programmer and a man who worked together in an office around computers, and they each had doubles—they had dopplegangers, dressed in black who were beside them all the time, or laying down or whatever, and while they conversed with each other about [robotically, flatly] ‘Do you have the program Catherine?’ ‘Yes I do but there are some bugs in it still that have to be worked out.’ ‘Well could you get that to me as soon as possible so that we can set it up and process some data?’ While they were talking like this, their doubles were doing all kinds of things—taking their clothes off, they were attempting to have sex with each other, they were rolling around, they were pulling out bottles, they were the sublimated computer programmers. And at the end of that one, the real people and their doubles become enmeshed together in an unresolved mass. People watching it thought at the beginning that it was about two people in a computer room. They didn’t know that there would be doubles and that the doubles would upset the reality of the ‘real’ people. Well, Emmett and Billy Murcott were both in that play. Neither one of them were very good performers—onstage.

Who was Billy Murcott?

Billy Murcott was a Greek American from New York who had run into or come west with Emmett Grogan. He had very curly black hair. He was new to drugs but he was very enthusiastic about taking drugs, believed drugs would change human identity, that he was in the forefront of that. Marijuana, LSD. Billy when I first met him was pretty interesting. Very verbal, vocal, so forth. For some reason over time he became less so. I’m not sure why. And his contribution was enormous. He wrote the essay “Mutants Commune” that was published in the Berkeley Barb. That’s Billy. And he named the Diggers. He was taking LSD and smoking pot, living in the Haight Ashbury, and began idealizing a future society. So he read a book on anarchism. And in it, the Winstanley group in England [the original Diggers group in the 17th century] was described. And he just thought the name was terrific for “I dig you” and “dig up the park”… y’know, the Haight Ashbury is right near the Panhandle of the Golden Gate Park. So we had the Park as our commons—the Diggers in England had a commons—and we had this idea of being free that is brought about through LSD. Free of precepts, prior understandings, etc. So Billy thought it was a terrific name for a group that would be, in the New York language and perspective that he and Emmett had together, they wanted the white equivalent of the black rebellion. Y’know, Why shouldn’t white people be able to have this too, whatever black people were doing. So they formulated an idea of starting a group called the Diggers, although they didn’t know what it would be like, on a roof watching the Fillmore burn during the Fillmore riots—the Fillmore was the African-American part of San Francisco—in 1966. They wrote together something that was like Martin Luther’s 99 Theses. They asked me what to do with it and I said, Tack it to the wall of the Mime Troupe office. I had just barely glanced at it. I was working for the Mime Troupe at the time. And so everybody came in one morning to the office and there’s this sheet that says [chuckles], this list of things: Fuck the country, fuck capitalism, fuck the civil rights movement, fuck the Black Panthers, fuck this, that, fuck pop music, et cetera, and the last one was: Fuck the Mime Troupe. It was signed “The Diggers.”

And I saw that and thought, Now these are two guys that have been through my guerrilla theater thing, where I’m trying to move theater from being on the stage to being in the audience. They are moving things into the street of the Haight-Ashbury. We could have a street theater where the street is the theater—where the street is the stage. And we can cause things to happen, because I’ve seen this, I’ve witnessed this. And we can do it on a large scale with all those people pouring into the Haight-Ashbury. (I lived in the Haight Ashbury at the time.) So I left the Mime Troupe, without very much commentary.

During that period, I had been down to Delano to see the way the Grape Strike Theater was operating. The Tulane Drama Review mistakenly advanced me some money to go down and write an article about the Teatro Campesino. I went and I saw that they had made a village. The strike was a description of the society that the union hoped to create. It had a free clinic, food, education, etc, housing. They were taking care of people’s needs. The union movement was always that—a strike was always supposed to be the theater of the achieved society that the union would bring. The strike is a struggle between the working class and the ownership class. It describes that struggle. It takes form in the strike, and then strike assistance to workers is the forecast of the future society that the union movement can bring about. Well, I was aware of that, and I saw it there. There was a theater, of course—the Teatro Campesino. But the strike itself was extraordinary theater. So Luis Valdez was busy promoting himself to me and to other people as a wunderkind of theater, and in a way he was, but the grape strike itself—la huelga—was the theater. [chuckles]

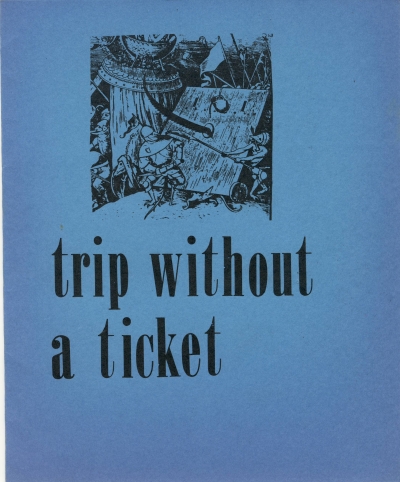

So I opened a free store in the Haight Ashbury. It was named “Trip Without a Ticket.” It was a store to exemplify the Digger credo, which was: “Everything is free. Do your own thing.” And we’re pulling now off of Anarchist history. We are being the Anarchist movement of contemporary American society. We’re exemplifying what anarchy could be in American society.

So, the free store is named Trip Without a Ticket, and I wrote an essay about it titled “Trip Without a Ticket,” which was one of the Digger Papers, which was later reprinted in The Realist. I sent it to the Tulane Drama Review, and said, I don’t know what happened to your money, but I know what happened to the article: this is it. Print this, and don’t be surprised. Well, they didn’t print it. [chuckles] They didn’t know what they had in their hands. And they resented me too for failing to fulfill my contractual obligation to be a journalist, which I wasn’t.

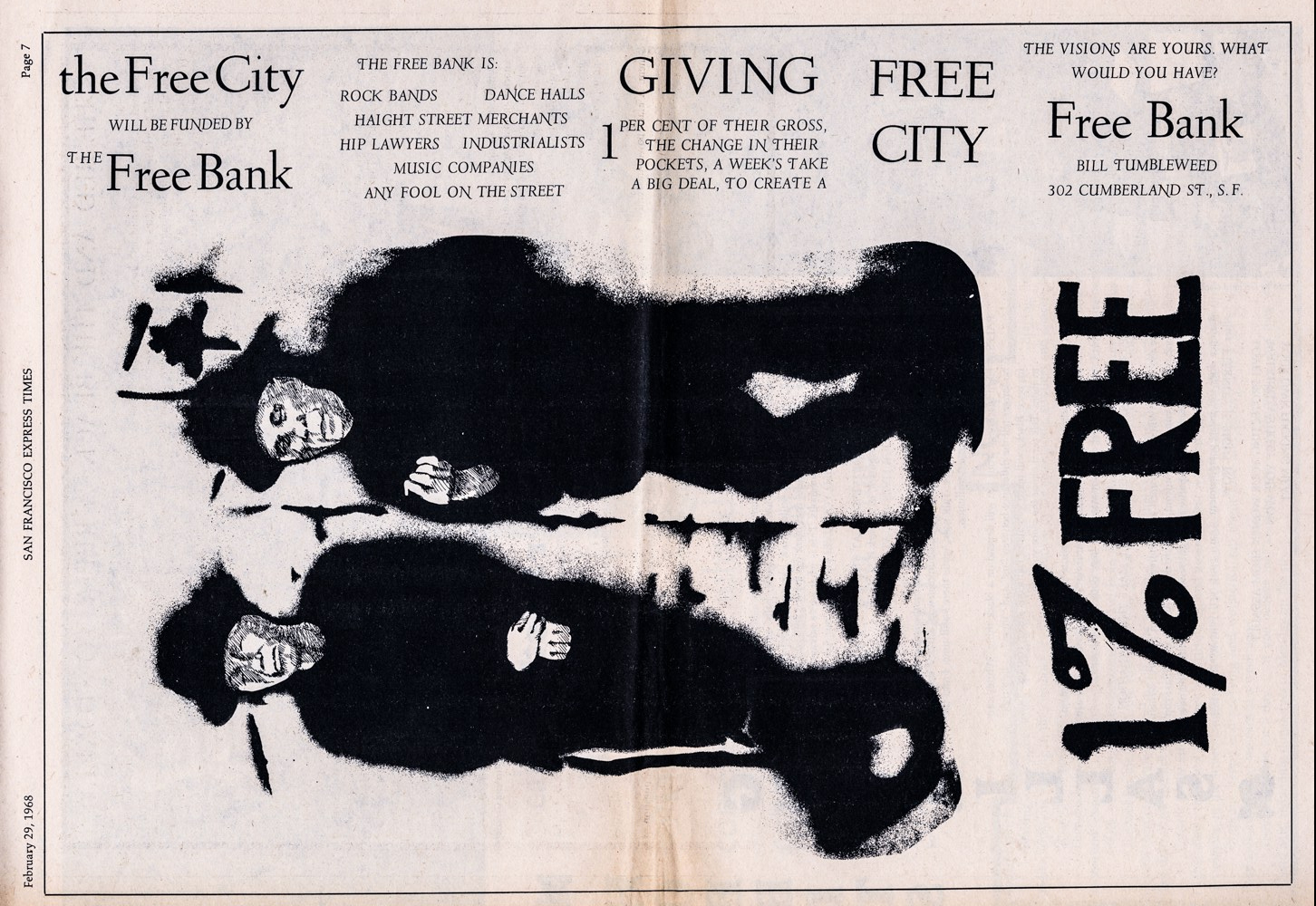

So now the Diggers are underway, and the approach is put “free” in front of anything you can think of and that would make it ‘Diggerly.’ How do you be a Digger? Well, think of something and put ‘free’ in front of it. For example, food. Put ‘free’ in front of food. Or, housing. Put ‘free’ in front of housing. Or energy. Or art.

For example: the tie-dye craze of the hippie generation. I know where it started. It started in that Free Store. It started with a woman who had been studying Indian fabric techniques. We were starting to get a lot of white shirts. People were dropping out and they were leaving their formal clothes at the door of the free store. So we would walk in in the morning and wade through these piles of white shirts. We had a super-abundance of them. This woman, whose name was Luna, said, We can make tie-dyes out of these. We said, What is tie dye. And so she showed people what they were. The Digger women looked at them and said, These are fantastic. We can make them ourselves, we can do it to all these shirts. So we began showing people how to do it. That became a standard activity at any Digger event after that, off in a corner somewhere someone would have boiling pots of dye and people, men and women, would be tying up shirts and tie dying them. And then this miracle would happen, you’d undo the cords and BOOM, these cosmic and amoebic bursts would occur. That was free art. Take the white shirt: it’s free. Do this technique with it: you can learn it, and it is art when you’re finished.

For me, the highest form of our free art were the street events that we did. We did events that were pageant-oriented events, but the audience didn’t know it was a pageant. They didn’t know they were in it. It was just happening all of a sudden, and the material to do it would show up, or the characters of it would move through the crowd.

Can you talk about doing free food in the park?

If you ask people who were there during the middle ‘60s in the Haight–Ashbury, during the advent of the Diggers, what they were doing, you will get different stories, depending on what their perspective is. Some men were there to hit on girls. That’s all they can think of from that period. Some people were there to be politically idealistic, and everything they’ll talk about will be framed in political idealism. I saw everything as theater. So from my point of view, giving food to people in the park was not just feeding the waves of liberated people coming to the Haight-Ashbury to identify themselves with the psychedelic revolution that was underway. It wasn’t just that. It was also a demonstration of an attitude—that food should be free. All food in the society should be free. It was a guiding ideal. From my point of view, the left didn’t have a guiding ideal—there wasn’t a place it wanted to go. We wanted to give it a destination. So we would give it a destination by enacting the destination. So everything we did, from my perspective, was a demonstration of this future world—in the present. It was like, Walk through it. Feel it out. How does it fit? What’s wrong with it? What’s good about it? The food should taste better. Yeah, right, okay, it should taste better. It should be fresher. Right. It should be organic. Those kinds of things. It should be homemade. Digger bread…should be made in a recycled coffee can. You should make it yourself. That would be part of the coming world, the new vision. The guiding vision.

So it wasn’t just enough to have food in the park. [smiles] The food in the park should be served inside a 12-foot square frame…that is, a picture frame, one that is so large that the human activity inside it will always fit. It will always seem to be part of a deliberate painting. And this frame should be aimed at the cars that are coming to work in the morning, so the commuters coming down Oak Street would see people getting free breakfast out of a milkcan within a 12-foot orange frame that we would call the “Free Frame of Reference.” Right? We really wanted to lard on the language and the symbolism and the theater of it. [laughs]

Everything we did was like that. We would set up situations at the Free Store where one magazine writer is interviewing the other one, and they’ve both been told that the other one is the manager of the Free Store. And they actually are going at this for five minutes, undoing this confusion for our benefit—they were performing for us. [laughs] Or people would walk in and say, Who runs this free store? And we’d say Well as a matter of fact—you do. Someone was running it, but now that you’re here, we’re leaving. [laughs] And we’d walk out. Wha—couldn’t I just take anything I wanted??? Yes, you could. Well, what if somebody wants to pay for it? Take the money. What should I do with it? Keep it. [laughs] The idea was not just to give away things free, but to create a theater where people could explore this notion of a free store. What would it be like if things didn’t cost money? How do you relate to them? How do you get them? How do you decide about them? Do you share them? How do you use it? Quite amazing to me, there were African-American women on welfare that would just sit there and wait for people to bring donations and quickly go through the donations as fast as they could to get the best stuff out of it and pack it in their own bag to take later and sell. And they were like, Do you people know you’re just giving me everything I need here? And we’d say, Great! Or, I actually saw this: we had a changing room that was really a place for sex. It was done in velvet and mirrors—it had a couch, it was really [chuckling] a very decadent changing room. Somebody came in, in uniform, regular Army, pulled men’s clothes off various racks, went into the changing room, came out, walked out of the place. I went over, opened up the changing room. His uniform was there. He’d deserted the Army, on the spot, and got the clothes for it: that’s how he used the Free Store. To me, that wasn’t a political act, it was a theater thing. He came in a solider and he went out as a civilian. [laughs]

I tended to see most things in terms of theater. I think most people, if they’re exposed to that perspective, can see this acting out as theater, without thinking it’s fraud, without thinking it’s fake. Nothing I ever did was fake, none of it was phony, but the name I gave to it was “life acting.” It was creating the condition you describe, which is a phrase that I read in a book titled Thespis [Ritual, myth, and drama in the ancient Near East by Theodor Gaster], about the annual journey the pharaoh of Egypt took up and down the Nile as a way of uniting the two Egypts, the upper and lower. He had a barge, and it would go up the river, and incidentally collect taxes. But people would bring symbolic things onto the boat that represented the area that he was in, or the nationality of the people, because you know the Nile is like 3,000 kilometers long, it’s really an enormous body of water. So people would act out who they were getting on the barge, and the pharaoh would act out the creation of Egypt as a unified kingdom by his presence. And they would give symbolic things while the tax collectors were actually picking up the bags of grain, they would bring a handful of grain to the pharaoh. So it’s all very symbolic, and the writer of this book said, and by so doing, the pharaoh would create the condition that was described: he would make a unified Egypt by unifying it through this trip, this ritual pageant.

Well, that became my ideal, to create the condition we described. And for me, the street events, and sometimes we did them inside, in buildings, but the ones I really liked best were street events. One of them was called “The Birth of Haight and the Death of Money.” And that one in particular had elements that were just unbelievable. It was unbelievable to see it happen on Haight Street. The entire street would be thronged with people who knew they were participating in some event, were not exactly sure what it was, but would see various elements of it pass along the street or the sidewalk. For example, a coffin, painted black, with oversized gold and silver coins, carried by black shrouded, animal-headed people. The animals are bringing a coffin full of money down the street, singing ‘Get out my life, why don’t you babe’ and people just cracked up. It was so funny, it was so them, they identified with it so much. They all got it. Think about the elements: they’re a little to the side of normal behavior or imagery. Black shrouded characters wearing enormous animal heads carrying an oversized coffin full of oversized money singing Chopin’s Death March, with pop lyrics, walking down the sidewalk, and everybody bowing in front of it, people spontaneously doing that. While people on top of rooftops are flashing the sun with rear-view mirrors that we got at a junkyard and passed out to people and pointed them to the tops of buildings, blowing penny whistles that we passed out to the crowd. And these things would come in waves. Suddenly the people would appear with the bags of pennywhistles and pass those out, and then you would start hearing pennywhistle music, where before you didn’t hear it. Or the rear-view mirrors would get passed out and suddenly light is bouncing around the street. And this is ten blocks of Haight Street [laughs] where this is going on. Thousands of people are involved in it.

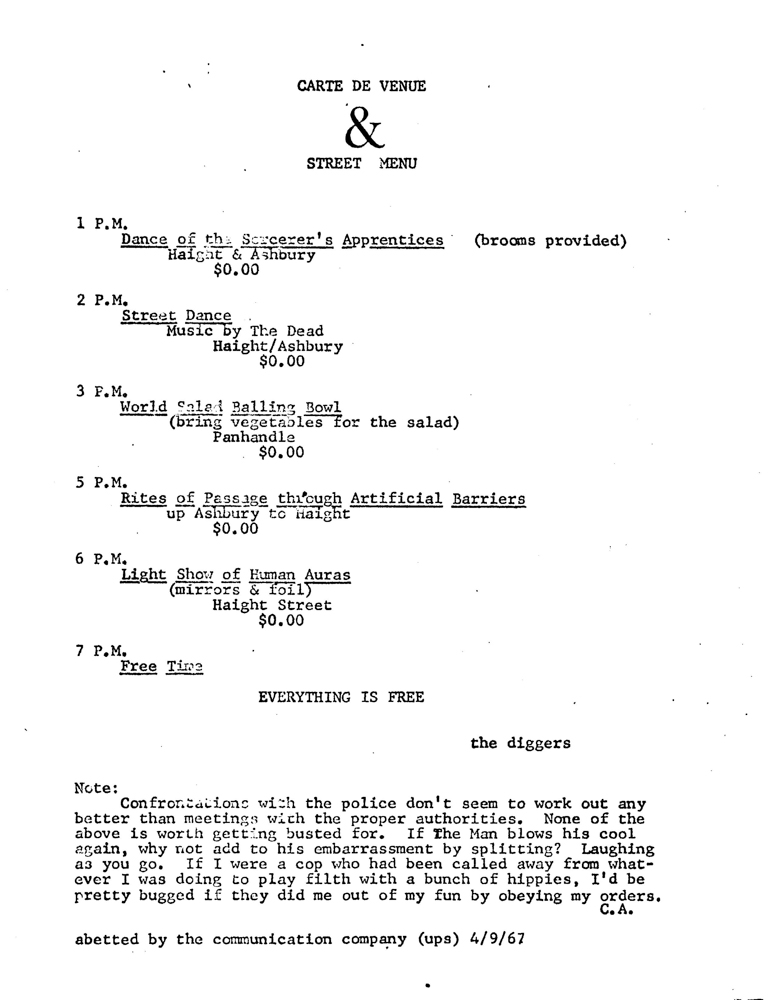

One time people were in the park, and we urged people, Leave the Panhandle, go to Haight Street, we’re going to be doing this event. I printed up something that said Carte de Venue [“your card to go someplace”] and Street Menu, and it was what was going to happen when you got to Haight Street, what was the course of events. In order to get to Haight Street from the Panhandle, people had to run through, and destroy, newsprint-sized, three-feet-wide paper…not banners, just newsprint. Bands of paper that were beautifully decorated with Paisley-style paint drippings. You had to break these—you had to destroy them—to get onto Haight Street. It was like that was the entrance fee, that you had to break your conception of what was a good or beautiful thing to get onto the street to do this new kind of theater. And nobody was told that. They just assumed I was right about that. They broke these things… [laughs]

One time at one of these events, women were on top of the buildings with a poem of Lenore Kandel’s, holding it up — this is above the street, three storeys up, very large, the same three-feet-high newsprint—we got this newsprint free, it was the end of a roll, when they make a newspaper they have hundreds of feet of this stuff left over, anybody can go to any print place and say can I have the endrolls, and get it for free—and the women are wearing incredibly gorgeous avant garde outfits. Avant garde: we knew they were avant garde because they were one-of-a-kind outfits that Levi Strauss had been trying out. They were like silver lame Levis, that kind of thing. And they’re reciting this poem of Lenore Kandel’s from the rooftops, holding it up so the people down below could see it and read along with them. [chuckling] Now that’s literature. Is that literature or what?

There was a certain point in time where the focus of creative energy that used to be in North Beach was no longer in North Beach—it re-emerged and it was in the Haight-Ashbury. There were so-called Beat poets, the San Francisco poetry scene, who retained all of their integrity, all of their critical viewpoint, and suddenly saw this psychedelic rebellion and quote hippie—that’s a phrase I do not like, ‘hippie’—emergence as being the children of their desires. It was what they wanted instead of the negative society that they had criticized. So we became the pro-active manifestation of the protest of the Beats. And it was very attractive to Lenore and Richard Brautigan and Mike McClure, Gary Snyder, they saw a lot of hope in it. Allen Ginsberg saw it as the manifestation of their idealism. You know, Americans have a continuum that goes from idealism to disillusionment. We all know what this is. We all have had both of them. And we all keep both of them to various degrees. And the Beats were already disillusioned, and were more disillusioned by Vietnam, the horrors of the civil rights scene. And all of a sudden, there’s this group of people saying everything is free, do your own thing, who have their own music, have their own art, have their own dress, and they saw them as being the people they created. So, they were very participative.

Kirby Doyle wrote a magnificent essay, titled The Birth of Digger Batman. Billy Batman [real name: William Jahrmarkt] was the person who owned the Six Gallery, which is where the reading of Ginsberg’s “Howl” first occurred. [Berg is in error here: Batman did indeed own a gallery, but it was called the Batman Gallery, it was located at 2222 Fillmore, and it did not open until 1960; its first exhibition was Bruce Conner.] That was Billy Batman’s gallery! And he and his wife had a child during the middle Sixties that they named Digger! You see, the connection is very, very clear. The Beats saw their children as the Diggers.

And there was Ken Kesey with the bus Furthur, parked along the Panhandle. That sort of manifestation.

How important was LSD for what was going on?

I don’t think the psychedelic rebellion would have happened without LSD. I don’t think the proactive manifestation would have had the courage to occur. The Beats would have done it, if they could’ve. The hippies did it, because they had LSD. LSD was so undeniably a consciousness-changing agent, and to go on that consciousness change, to undergo it, and to come out on the other side, and not be ravingly insane, meant that you could turn reality upside down. Reality could be turned upside down, and good things could come of it. It could be done. The Beat ethos lacked a magical ingredient. It would’ve taken an act of magic to change society. That’s why so many Beats were enormously depressed. By the Civil Rights phenomena — not the civil rights, but the repression. And the war in Vietnam. It was like, How could this happen? How could you have a Democratic president and be crushing black people on a daily basis, and bombing, and poisoning a whole nation? How can you change that? It would take an alchemical act, or substance, or magic wand, to change that. [gestures, here’s the answer:] LSD.

I never will discredit LSD. I won’t join the legions of people who feel that for some reason having lasted through the Sixties they can now join the mainstream and repudiate LSD. I will never do it. It was a magic wand. I thought the Diggers were social LSD. I called the Diggers “social acid.” Everything is free/Do Your own thing — everything can be turned upside down AND BE BEAUTIFUL. In our society, everything costs money, there’s no free lunch, and you’re not supposed to be a total individual—you’re supposed to cooperate with society and be productive, in corporate terms. To say ‘everything is free’ repudiates that. [To say] ‘Do your own thing’ gives you the authority to be an artist—[to realize] that everybody is an artist, which, you know, we all believe. At least, I believe. What is it, in Bali, someone asked the Balinese ‘what is your art?’ They said ‘we have no art, we just do everything as well as we can.’ So LSD gave people that authority, it authenticated that positive possibility. And everybody that was involved with that thought — that, there, was a revolution of consciousness afoot.

“Civilization is up for grabs”: Berg gives a brief, explosive exposition of the situation in Summer 1967, starting at 33:16, with a second one starting at 41:58. (From CBC documentary series, “The Way It Was,” directed by Don Shebib)

Were the Diggers missionaries for LSD?

The role of the Diggers at the Human Be-In was to pass out 3,000 tabs of LSD. They were given to the Diggers by Owsley. Not personally. Owsley wasn’t a person you saw. He knew that everything he was doing was at great jeopardy. As a matter of fact it was two very large African-American men who came over to the Free Store with the 3,000 tabs of acid, like a pie box full of it, and said, [in deep voice] This is from Owsley. [chuckles]

The Diggers communicated via broadsheets put out by the Communications Company (Comm/Co). One of the guys involved with that was Chester Anderson. Who was he?

Chester Anderson was a Beat consciousness type who was in total rebellion against his Navy/military family. I believe his father was high-ranking, maybe an admiral. He had dropped out, and he was older than many of the other people who were involved with the scene. I would imagine the age range of the Haight-Ashbury was about 20 to 30. I was a little older, he was at least ten years older than I was. And he was a Sexual Freedom person. He had his own sexual preference issue. And he had acquired a Gestetner machine; Gestetner was an early Xerox-type printing machine, very well made by the way, that used color. At that time, Xerox was not in color, but Gestetner was. [smiles] I think he had obtained it under a false pretext. Anyway, he and someone who worked at Ramparts magazine, Claude Hayward, began something they called the Communications Company. They were struck by the Digger ethos, and they were going to be the ‘free’ printers. The form that they used was to produce daily or occasional 8.5 by 11 or 8.5 by 14 sheets of paper with various messages on them, some of them very helpful to people, like numbers to call if you had an overdose, or numbers to call for social assistance. But a lot of them were ones composed for example, for street events, or composed for expression, or had poems. When Martin Luther King was killed, David Simpson made one that had a splash of red, as blood, and the words, “Goodbye, brother Martin. Today is the first day in the rest of your life.” And we passed that out in the street. A lot of Brautigan’s poems first appeared that way. A poem that was rejected by the Oracle newspaper for its overt political content, written by Gary Snyder, was titled “A Curse on the Men in Washington, a curse against the Vietnam War.” A curse on the men and their children, by the way—that’s why the Oracle thought it was too far out. Anyway, we first published it as a street sheet—I know, because I got that one published. I imagine they did several hundred.

What was the relationship with the Grateful Dead?

Some of the Diggers, including myself, went to their house. They had a house on Ashbury Street, everybody knew where they lived, and we invited them to come to a free event that we were gonna do in the park. We’d begun doing free events, along with free food. We took over the park! We acted as though it was our park. The Panhandle was our commons. So we told them we had events there and that we were going to have one on the weekend, and that if they would come, we would do everything we could to accommodate them. We’d get a truck for them. If they wanted a sound system, we’d find a sound system so that they could play. But they did not want to play. The members of the group that I heard conversing about it were saying, Why should we do this? Why go out there in the middle of the day? I don’t get it. What is this all about? Won’t we get busted? That kind of talk. As I recall it was Danny Rifkin, who was one of their road managers and started their fan club, who said, This is it. This is why you are a band. This is going to engrave you in people’s memories. We’re gonna get so many fans from this. You’re going to get your dream of audiences. Get on that truck and go to that park and PLAY. And all that happened. We wanted them there; we invited them; we helped them get there; Danny convinced them; and they showed up.

Then after that, they were sometimes available for free concerts. So was Janis [Joplin]. Janis was at an indoor event we had called Free City Convention. We had a Free City Convention [like a conventional political convention], where people had signs that said things like State of Innocence; y’know, State of Grace. [laughs] We burned money. And I remember all that going on and Janis singing at the same time. And Stanley Mouse painting on the pillars inside the Carousel Ballroom. That’s where it was, the Carousel Ballroom. And everything from teenagers from Hunter’s Point to people in Army uniforms were at this event. Wonderful.

What about The Invisible Circus event at the Glide Church?

While I was still at the Mime Troupe, a group of us thought it would be a very good idea to start an artists’ organization that would make statements about social change that artists supported. We called it the Artists Liberation Front. The Artists Liberation Front had a couple of events. Small-scale benefits. There were some notable people involved. Brautigan was one, Ferlinghetti was at some of the early meetings of it. I’m sure that’s how Lenore Kandel got swept into the Diggerly Do. At any rate, the Artists Liberation Front morphed through a couple different identities, but at a certain point the idea was that there should be a massive event—a city-shaking event—and it would be called The Invisible Circus. And at it there would be people who were poets and musicians and actors and writers and painters and members of the general public and it would be to manifest this free, creative identity and it would have a Digger overlay. So essentially the Diggers brought it about. And the Diggers worked for it in concert with various artists, who thought of themselves as artists but also as social/cultural activists, among whom, primarily, was Lenore Kandel.

There was someone at Glide Memorial Church—there was a person there who was very straight—blue suit, short hair, but he was teaching the congregation about ‘sexual deviation’ and he was showing pornographic films and he had lecturers that were gay and lesbian lecturers, and he wanted to have a major role in this. He thought this would be good for changing the identity of Glide Church. On its own, the Methodist body in the United States decided that this church in San Francisco would begin serving minority groups and the poor. They made that decision. And they got rid of the top personnel and anointed a blue-suited, short-haired, thin, African-American preacher from somewhere in the South named Cecil Williams. It was going to be one of the first mainline, previously white churches now overseen by a black minister. So in this interim period, Glide Church is available and one of the key people operating it is the man who’s trying to teach about deviant sexuality, or ‘alternative’ sexuality. We approach him and say why don’t we have this event in your church. Glide Church is a really large building. It takes up maybe a quarter of a block, or, a corner of a block, both sides of the block for some distance. It’s really quite large. Had a lot of spaces in it—several floors. An elevator, going from floor to floor. And over time, mostly because Lenore Kandel convinced them they had a sacred, spiritual obligation to serve the liberation of people and that the Artists Liberation Front and the Diggers were doing that, that we were on a mission to accomplish the liberation of people, and that this was the spirit of the Church, eventually convinced them that we could have this church for 72 hours to do whatever we wanted. And every time they’d say, “well, no such-and-such,” Lenore would say, ‘Now wait a minute, that isn’t liberation. [pointing finger, speaking gently] Every time you say no, you’re not liberating. Come on, get used to it. Loosen up. You must liberate.’

So now they turn the whole Church over to us, for Friday, Saturday and Sunday. And we went absolutely mad. I decided that every pet annoyance I had with society, I would turn around. I was annoyed with the space program, so there would be a room that had newsprint, completely as an artificial wall. People would be brought into this room. They would not know that this was an artificial wall. They would watch NASA footage of the earth, and at a certain moment, belly dancers would crash through the paper, bellydancing to the music of the Orkustra. The chamber Orkustra. Who are playing Middle Eastern-sounding music. And the bellydancers would move amongst these people, who, moments before, had been watching the space program’s vision of the earth.

That’s one of the things I wanted to do. The other one was, I wanted to have an obscenity panel. I remember convincing the church people that this would be a great thing: an obscenity panel where a minister, an ACLU lawyer, a writer on sexuality, someone else, would start talking about censorship and pornography and obscenity in front of a glass case that was in this wall. On the other side of this wall was an actor who took his clothes off and began playing with himself [laughing] so the audience is watching this panel and seeing through this panel to seeing somebody being obscene, because you know obscenity panels never had anything very obscene about them. And in the middle of all this, someone who was a fireeater would walk over to one corner and start blowing flames out of their mouth [laughing]. I think I was dressed in scrubs, hospital scrubs, as the doctor, you know, to talk about obscenity.

Lenore was saying, I want to do something but I’ve been so busy organizing things, I haven’t thought of something to do yet. I think what I’ll do is be a palm-reader. I said, You know, it’d be much more interesting if you did foot reading. Why don’t you have people take off their shoes and put their foot up in the air. And we’ll have a foot [diagram/poster] that says Happiness, Joy, whatever, and you’ll be a foot reader. Just pass yourself off as a foot reader, convince people that you can read feet. So of course she was totally charmed by it. She did that. She also—it turned out that in the Church there was a room where brides get ready for weddings, and Lenore took that room and put KY jelly there, and candles, incense, silk and satin, and low lights, so that it was a seduction room. And it was used for seduction. Emmett filled an elevator with shredded plastic. So you pushed the button [laughing], the elevator door opened, it was like waist-deep in shredded plastic. I think it was clear plastic, and white plastic and red plastic, shredded, in bands. [laughing hard] And you had to fight your way through the plastic to ride on the elevator. Brautigan decided that his event would be to have an instant publishing service, called the John Dillinger Computer, and for this he would use a Xerox machine. You would write a poem, he would run in, put it in a form that could be read, and turn out copies of it and pass it around, at the same time encourage somebody else to write a poem. Everybody writing poems and then publishing them on the John Dillinger computer. Someone else got a hold of all the films of the sexual variation class and opened up a blue movie theater in the church, a pornographic theater, that just ran continuously.

And I have not yet mentioned most of the activity. I didn’t see it all because I was involved with overseeing these events that required coordinating the fire-eater with [laughing very hard] the person playing with himself. Takes a lot of coordination. So I didn’t see it all, but at various times I saw Mike McClure walking around with an autoharp, singing his poems. Hells Angels moving through it. There were a lot of military personnel because Lenore had decided that the primary target for this should be militarism. Because militarism was so anti-liberatory. So she put out flyers, she had them distributed at Army bases, Navy bases, Marines, to come to this event, in order to experience liberation. So Hells Angels and poets and semi-naked or fully naked people, there was one gorgeous woman who took all her clothes off and did belly dancing, people made a circle around her, she was just so beautiful that no one touched her. It’s so interesting to see that phenomenon: that if someone nude was sufficiently in it, that they could have transcendental manifestation, and people, instead of grabbing at her, would stand back and just look at the beauty of it. Which happened. In fact there are photographs of her with people standing in a circle, just staring at her.

The place started crowding up with sailors, both in and out of uniform, soldiers of all kinds, everybody from the Haight-Ashbury. It got very hot. This was in the winter. It got very hot inside the Glide Church. So we threw all the doors open. So now you’ve got all the people in the Tenderloin coming in, which is homeless people, and people dealing hard drugs on the street. They’re coming in. Cops got interested in this. [chuckles] In the spirit of helping to manage this event, I go to the door where this cop is standing, door’s wide open, he said, What’s going on in here? I said, It’s a church service. It’s a church social. It’s a social event of the Church. He said, Uh huh. [squints eyes] You know, the doors are wide open? Anybody at all can come in and there are a lot of characters in this neighborhood. I said, Indeed. Yes, I believe this church’s new purpose is to serve the neighborhood. He said, I just want to make sure you know what you’re doing, cuz there’s some really scary types out here. And all this time he’s looking over my shoulder, looking inside. One thing about San Francisco, when the cops relax, they do relax here. They’re not on 24-hour fascist duty. And he’s trying to see in because there are naked people in there, and all of that. And eventually he says, Well just as long as you know what you’re doing. I said, We do. We will be doing this all weekend, and it’s serving a valuable purpose. And he left it alone.

So it goes on into the night. It started at something like 7 o’clock. For us it started during the day we had to get underway, and all of us laughing because we’re going to be pulling this off. They let us have the Church for this! And we know some of the things people are planning and can’t wait to see them. Some of us would run from one thing to another, say [waving hands] Is Brautigan doing the Dillinger Computer yet? Is Lenore doing footreading, I gotta see this! Have you been to the bridal room? Did you see what Lenore did in there? Wonderful, wonderful event.

It got to be something like midnight or 1 o’clock, and it’s too much for the Church authorities. They somehow get wind of what’s going on, and they want to close it down. Well, closing it down means you’ve got to go to every room and pull these people off of each other that are having sex, go into these rooms full of Hell’s Angels and sailors and tell them to put down their whiskey bottles and [laughing] go home. So it took the rest of the night to clear the place out, and then there was an incredible mess, from their point of view. Lenore was still, We did a very good job of liberating the people, here. And she’s sincere! I mean, there was nothing insincere about it. From the outside, if you were looking at it, you’d think it was almost like practiced that she would do this. But it was coming from her own integrity.

So by Saturday, dregs of things are happening. By Sunday, it’s closed down. And Cecil Williams shows up—Cecil Williams, the product of the Civil Rights movement, in a very anointed position now, to be running this formerly all-white church, in a mixed neighborhood of the city, he’s going to be the integration personality, he has to get his schtick somewhere. It’s not going to be Bible-thumping. Y’know, you’re not gonna Bible-thump for the drug addicts and hippies and whatever are coming to Glide Church. We felt we had loosened the church up for Cecil Williams’ eventual renown. He has a tremendous amount of renown for wearing African costumes, having choruses that are mixed race and of course giving away free food. Quite an indentation into that Church scene.

Can you talk about the SDS meeting in Michigan that you and other Diggers attended?

In early 1966, the Mime Troupe had become a bastion for the New Left. In fact, the New Left Review magazine was sharing space with our studio. Things from the New Left were always passing through the office, including the Port Huron Statement, that had been written by Students for Democratic Society [SDS]. I actually read it. Most of the actors in the Mime Troupe did not. As far as I know, none of the Diggers ever did. But I read it. I thought it was watered down. It was progressive, like the Progressive Party had been, in the U.S., whereas most of us felt that a revolution was underway. By the time the Diggers were rolling in the Haight six months to a year later, we were sure we had part of the answer for the alternative society to be. And at that time SDS was going through a leadership and affiliation crisis. There were SDS people who wanted to be violently active, and eventually the Weather movement came out of that as well. Well the people who remained behind in Students for Democratic Society and did not become more militant wanted to re-define themselves, and they had a conference that they called Back to the Drawing Boards. And I learned that it was going to be held and I thought this is where we should have our New Left encounter, for the Diggers, should be at this event. So I convinced Emmett, Bill Fritsch and Billy Murcott to go with me to Denton, Michigan and present the Digger alternative as part of the future that Students for a Democratic Society should strive for.

Somebody supplied a rented car, a very large station wagon. So off we head for Denton, Michigan, and along the way Billy Fritsch and Emmett Grogan got into a “man” competition type of thing, about who could drive better, who should drive, etc. It bored me. Billy Murcott was smoking pot in the back, he didn’t really care. At that point Billy has settled into his ‘happy hippy’ role. And so we hit a small rural road, and the argument is how fast you should drive on a road that’s mostly gravel, and they’re screaming and yelling at each other. Emmett was driving and he hits a hill, and the car partially took off and we ended up in a creek, with water coming in over the sides of the doors, and the four of us sitting there, and Emmett and Fritsch begin yelling at each other about whose fault it was. You made me do this by yelling at me. You did it because you can’t drive worth shit. So I’m looking at Billy Murcott like These guys are completely out of it, let’s get out of this car. [laughing] So we crawl out of the windows and we wade up to our waist to the bank. I’m looking at a white station wagon with two people arguing in the front seat in the middle of a running creek in a part of the Midwest that I know nothing about, the Northern plains somewhere. Murcott and I are yelling Get outta the car, get outta the car, it’s gonna fill up with water, it might float away. So they finally get out of the car. Now the argument is whose fault is this and who is going to take the blame for this, with the police and whatever. I want to get to the conference. I don’t care what these guys are yelling and screaming about, I want to get to the conference. I want to make some kind of presentation there. Heroically, Fritsch says, or maybe to one-up Emmett one more time, he says I’ll take the bust, I’ll say I was driving, I’m going to go to a phone right now, tell ‘em where we are, tell ‘em that I was the driver. We all knew that he had a record. Prison record. He was a felon, which meant that that would come into the consideration—a crime had been committed, and a felon had committed it. So I said Okay, if Fritsch takes the fall for this accident, and he gets into some scene about it with the police, obviously they’re gonna have a lawyer of some kind at this meeting, so we’ll get a lawyer and get him out immediately, maybe before the police find out about his record.

So, we get a ride in a tow truck, we go to the conference, the three of us. Billy goes to jail. We walk in the door and say We need a lawyer immediately. At the time Tom Hayden was giving one of those puerile speeches that Tom Hayden is capable of giving. And Todd Gitlin is recording everything into a tape recorder—Todd Gitlin of the book The Sixties fame—and people are sitting around staring at their star, Tom Hayden. I’m stating it the way we saw it, because we’re having this real-life drama occurring, and there’s something crucial involved, which is how long Fritsch is gonna go to jail. So we come in there, We need a lawyer. Well, people are talking here, you can’t just come in, who are you? We need a lawyer. One of you must be a lawyer. If you’re a lawyer, raise your hand. Somebody raises their hand. I say Okay, here’s the deal. There’s a rented car in the creek, our guy’s in jail, he’s a felon, if they find out they’re gonna give him a lot of shit. The political act right now should be to get him out of jail. So that guy goes off.

Now people say, Who are you people? And I say I’ll tell you if the guy with the tape recorder turns it off. You, will turn off your tape recorder. But I’ve got to record all this for the purpose of history! No. You’re not going to record anything that I say. I’m just going to talk to people here. Turn off the tape recorder. It wasn’t that I was afraid, I just didn’t want it to be historicized that way. It looked ridiculous to us to all be sitting around, pretending to be this political organization. It looked ridiculous. [chuckles] Right, so the Diggerly act was to turn off the tape recorder. The guy did, very reluctantly.

Now I asked Emmett, what do you want to say. He said, Nothing. Billy Murcott said, I wanna play tambourine. I said, Okay I’ll tell you what we’re doing in San Francisco, and this is what we think is a good direction for SDS to go down. You should become Diggers. This is what we do. I gave this long rap. Well the one who wanted to record it was really furious now because he wanted to have recorded that. The guy next to him, in an Army fatigue jacket, says, That’s fantastic. I’m going to do what you do. My name’s Abbie Hoffman. I’m tired of this civil rights plain existence. We should be having fun. We should be dressed up, we should be doing these things, you guys are on the right track, you’re fantastic. I’m going to go back to New York and do what you do. The rest of you—you should go back and do what they’re doing. So he became [raised eyebrows] a little bit of a creepy ally.

Hayden was really disinclined to have anything to do with us. We must have smelled like the devil, like sulfur and brimstone. Fritsch gets out of jail, he comes in. He starts crawling around on the floor, saying ‘Which – one – of – you – girls – wants – to – fuck -meeee?’ [laughing] And he’s talking to social workers and elementary school teachers? Oh, Billy. That was his way. [laughs] Anarchy by act! Anarchism by the deed. So then we got back in the car and argued our way back to San Francisco. And to a large extent, the other three really didn’t know why they’d done it, and what they had done. They weren’t following it. Fritsch was in a state of rejecting communism. He’d been a longshoreman and a merchant seaman. And his best friend’s mother and father were figures in the English Communist Party. They were looking for an alternative to Communism and anything that sounded remotely political put him off. Emmett was apolitical. I think he’d been subjected to too much Irish Revolution stuff. Probably his family was IRA supporters. They were working class Irish. And Murcott, it’d never been part of his life. On the other hand, I saw us as having a historical anarchist role to play. I’m not sure of everything that came out of it. I know in the book The Sixties, Gitlin says that I personally destroyed SDS, which I think if true, that means that anybody could’ve pushed it over. [laughing] If I pushed over that entire organization, it was ready to fall.

Almost all the Diggers made forays of one kind or another. For example, someone gave us a piece of land that we called ‘Free Land.’ There was a trip up to take a look at it. There was a trip to see the land that was going to become Black Bear Commune. People made trips to fields that had been harvested to glean them for vegetables and produce that would go into Digger Stew. I wanted to go to the East Coast after we had done the Denton, Michigan thing. We knew that we would start having a presence on the East Coast, and sure enough a group called the New York Diggers started with the painter Martin Carey and his wife Susan and Abbie Hoffman and for a while Keith Lampe, who later changed his name to Ponderosa Pine. They were all members of the New York Diggers. And they did similar things. They had a free store on the Lower East Side, they did some events, etc and we wanted to check them out to see to what extent we were kindred.

At the same time, word came that Alan Burke, a particularly aggressive TV shock jock for that era, who had a program called The Alan Burke Show, on which he performed vivisection on the guests, wanted to have a Digger show up to represent the hippies. Somebody on his staff had researched hippies and come up with the Diggers. Nobody felt particularly able or capable to do this, but I thought it would be a great event, I thought there was a way that I could twist it around, once I got the lay of it, which I never really got to do. I met Paul Krassner, he knew about the Diggers in New York, he wanted to know about us. He got very turned on with us and later put together the Digger Papers out of various Communication Company publications.

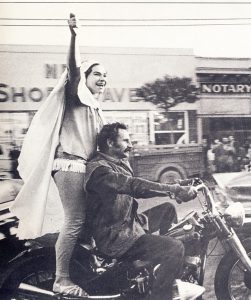

Anyway, eventually it’s go on the Burke show. I brought as a prop an antique pistol. The kind of pistol that’s a cap and ball, Revolutionary War-era pistol. I kept it in my jacket, with the butt sticking out. I also arranged to have one of the women Diggers be there with a pie that they would throw in somebody’s face at some point. So I go on the show. The first thing that happened was in the green room for that period, there was someone who was promoting himself as a representative of the hippie generation. He wanted to be, he was a New York hustler type who wanted to be a media personality. So he was asking me questions: Do people really smoke banana peels to get high? That kind of thing. So I saw that this is the image that the staff had of who we were, and they were not going to be ready for anything that I was going to do. So they say Come on the show and I come on out, sit down. ‘I’m Alan Burke.’ ‘I’m Peter Berg.’ And I looked at the audience and said I’m going to be talking to the audience all the time that I’m here. Never looked at this guy [Burke] again. So he’s asking me questions and I just began talking about what I wanted to talk about. I don’t remember all of it. A certain amount of it was repartee, like I would take off on something he said and say something completely different, so that people could see that I could be a free individual, even within his format. I felt that television was extremely coercive. So what I wanted to show that. At one point he says that he’s not having any luck getting his questions answered, maybe if people in the audience ask questions, I will “deign to answer them.” So a woman comes up to the microphone, says I think you people are making a lot of noise about nothing in particular and I think you should tell us why should you be free, I don’t get this. Burke says, Don’t you have a leader named Emmett Grogan. I said, No, there is no Emmett Grogan. There is a woman named Emma Goldman, and she happens to be here tonight. Emma, would you come and explain to this woman with a pie what we stand for and why we should get what we want. And the woman, Natural Suzanne, a particularly strikingly good looking woman who liked wearing fur coats for reasons I’m not sure of, it was winter, comes up with the pie in the box, opens up the box, takes out the pie and pushes it in this woman’s face. [laughing] So the whole audience is outraged! Just an innocent woman asking questions, but by the way being very demeaning, about who we are. And Burke is, What just happened on my show? So I looked at the camera and said to the cameraman, would you come over here, would you put the camera on me, Hey!, [whistles], You got me? Good. Now turn the camera up to the top of the room. Up to the top of the studio. Let everybody see the girders. The guy’s going okay. He moves the camera up. I’m looking at the monitor and he’s showing the girders and the lights and everything that’s hanging, all the wires. This is what the television studio is, it’s actually like your television SET! People watching this: this is a television SET, that we’re in, that you’re watching ON your television set. Do you get it? They’re broadcasting a television set to your television set. Now, would you, bring the camera on me now, put the camera on me. Got it? Good. I’m getting up, and I’m going to walk out that door. Would you show the door that says ‘exit’? Show the door. That’s it. Okay. Good. Back on me. Thanks.

I’m going to walk out the door, and when I walk out the door, I want you to turn off your television set. So I’m going to walk out of this television set, and you’re going to turn off your television set. See, we can do this. We have the power to do this. Here we go. I’m getting up—keep the camera on me—I’m walking toward the door. You got the camera? Thanks. I’m opening up the door. Goodnight! Goodnight, everyone. Opened up the door and walked out.

I have no idea what happened afterwards. I didn’t stay. I asked Natural Suzanne, and she said she felt she had to get out of there fast. [laughs] Then I thought, This guy asking me if you can get high smoking banana peels in the green room, [laughing] he’s going to come on, and he doesn’t have the wit to know this guy’s gonna take him apart.

Amazing.

What was the relationship between the Diggers and the Hells Angels?

As with asking anyone about the Diggers, you would get different answers as to what their purpose was, the relationship between the Hells Angels and the Diggers were similarly a hugely…It had a huge range of possibilities. For example, some of the Digger women had affairs with Hells Angels, so to them, some of the Hells Angels had been their lovers. Anything else about it didn’t particularly matter, that was the relationship.

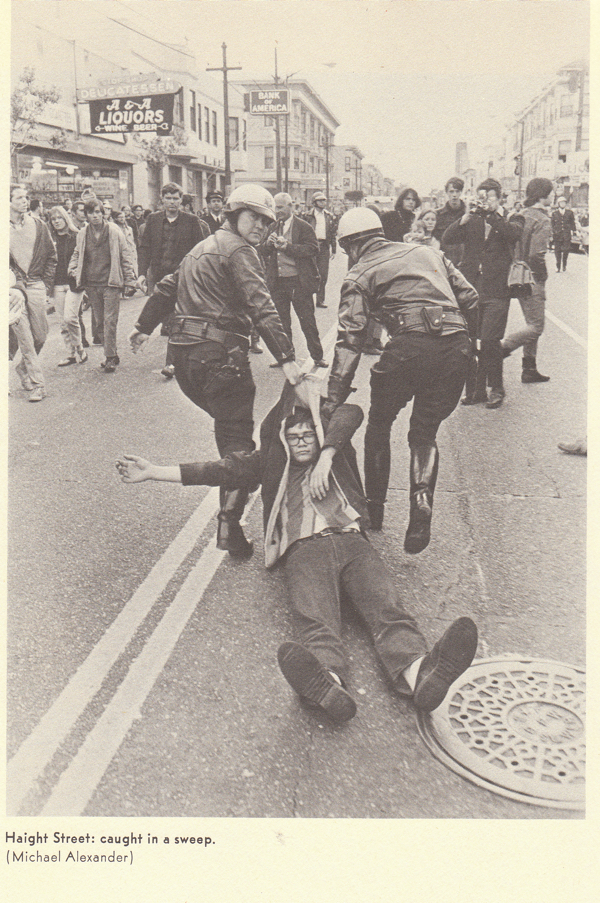

My relationship with them was that I knew we had to be heavier than we were. The Diggers called themselves ‘heavy hippies’—it meant they weren’t flower children. We were capable of carrying out acts and confrontations with the police that were above the level of flower children. We deliberately provoked the police on occasions. I designed a street event that stopped traffic deliberately for which all the characters were arrested. And went to trial. And we were acquitted. The acquittal made the front page of the Chronicle and became sort of a totemic image of the psychedelic rebellion. Flower children didn’t do that. Flower children didn’t have anarchist history, or connection with the anarchist political tradition. It should be clearer than it is, that when the overthrow of kings was a prospective activity for the French, what would replace the monarchy was as often thought of as an anarchistic option as a democratic option. Anarchism had a very good reputation in Europe for at least 150 years, as a real option. Jean-Jacques Rousseau is an anarchist; Jean-Jacques Rousseau is considered to be the founder of the philosophical idea of liberty. So anarchism had a tremendous reputation and a huge number of adherents, especially in places that were more peasant-dominated than others: Russia, Italy, Spain. The anarchist tradition still survives in those places.

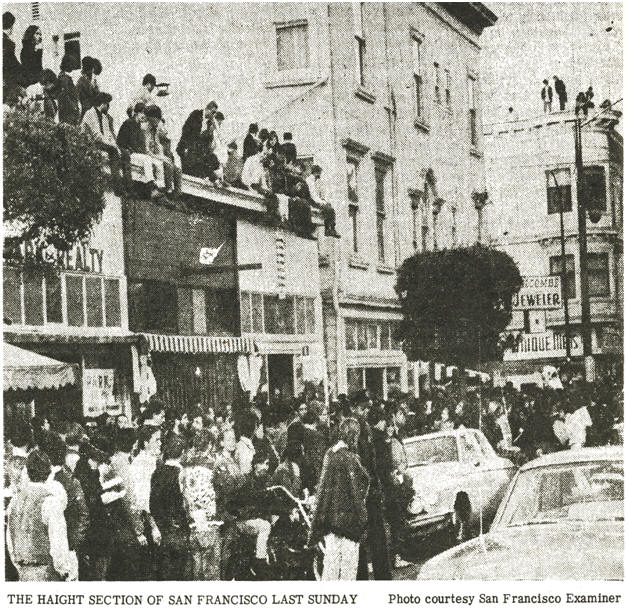

What was going to happen ultimately with authorities, and in fact happened, was that the police were the agency that closed down the Haight-Ashbury. You will read euphemisms, or excuses, for the demise of the hippie rebellion as being the introduction of hard drugs, or ‘the bloom was off the rose,’ or blahblah. The police closed down the Haight-Ashbury. They brought in mercury vapor lights that burned all night, bright orange. It looked like the Berlin Wall on Haight Street. They made the street one-way, so that traffic barreled through it. They put paddy wagons through it about every 15 minutes, picking up people from the street.